To Matthew Atkatz, the college snapshots he kept in shoe boxes in his closet for years raised a koan-like question: “If they are sitting in a box,” Mr. Atkatz, 46, said, “do they have any meaning?”

They do, it seems, when displayed alongside hundreds of forgotten snapshots collected from other art students from the grunge years on an Instagram feed called 90s Art School.

Since last April, Mr. Atkatz, who graduated from the Rhode Island School of Design in 1997, has collected thousands of old snapshots and Polaroids from schoolmates of that era and given those predigital artifacts new life in the digital era.

What started as a visual class reunion of sorts for Mr. Atkatz and a few friends, has evolved into an art project exploring the ways in which young artists chronicled their lives and aspirations through photography in an era before social media. The pictures have an unselfconscious quality.

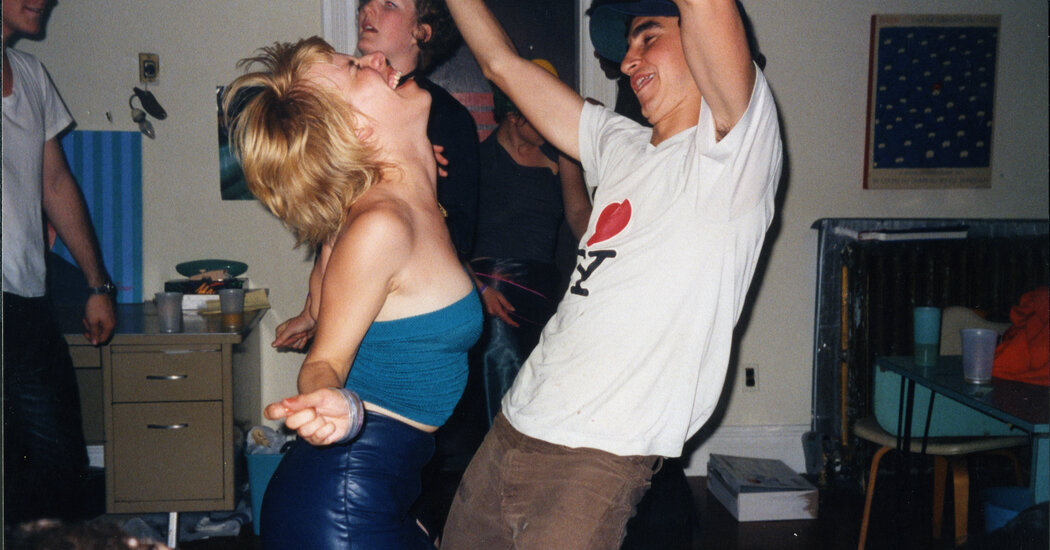

With aesthetically attuned art students as the focus, the feed is a tableau of Generation X fashion signifiers: flannel shirts, black eyeliner, bleach-blond hair, cropped tops and baggy jeans. “There were goths and hippies and kids that were into ska or straight edge,” said Mr. Atkatz, who now runs an advertising agency in Miami with his wife, Liz Marks. “When we went to a show we watched the band, rather than a screen,” he said. “There were more delineated tribes in the ’90s. In some ways, I feel like social media has homogenized culture.”

The paradox, of course, is that this visual rumination on the pre-Instagram age is only possible because of Instagram. “It was like we expended a decade’s worth of energy on images that no one has seen,” Mr. Atkatz said. “I was interested in trying to create joy using that latent energy.”

While the feed includes only submissions from former RISD students, so far, Mr. Atkatz plans to open it up to ’90s students from other art schools, with plans for a gallery show and a book as well.

Even for those who did not attend RISD during those years, however, the feed has anthropological value.

“Folks that are young that are in art school have been reaching out to me and saying, ‘Oh wow, thanks for sharing this — it’s cool to see what art school was like back then,’” Mr. Atkatz said. “I think young creatives enjoy it, just because the ’90s were a fun moment in history. It was a simpler time.”

The ’90s may have been a simpler time technologically, a fact underscored by the cathode ray tube television sets and first-generation Apple Macintosh computers that populate the photos. But those years were hardly a more innocent time, if all the shots of students swilling beers and puffing on cigarettes are any evidence — not to mention crowd surfing at club shows and wrestling half-nude at underground warehouse parties.

In weeding through thousands of submissions, Mr. Atkatz made a point of emphasizing low-fi casual shots.

“Instead of images of the art, or creating stuff in studios, I’ve focused on the parties, the nightlife and the behind-the-scenes shots of what life was like back then,” he said. “They feel much more candid than the way people treat social media today.”

In that spirit, Mr. Atkatz has denied requests to tag people in the photos on 90s Art School. He includes first names only, in captions, and even leaves out locations, “which, he said, “lets the photos just be about the photos, rather than becoming a promotional platform.”

This is not to say art students of the ’90s were naïve to the concept of self-marketing. “Young people today are trained to think of themselves as a brand, because of social media,” Mr. Atkatz said. “Warhol was probably the originator of that, and we were all influenced by him back in the ’90s. But I don’t know if the pictures were such a critical piece of that.”

Even so, RISD students were grounded in the visual arts, and trained to develop an eye for subject matter, color and composition, which carried over into their personal photography, said Whitney Bedford, 45, a painter in Los Angeles who graduated in 1998 who has submitted to the feed. “It was an art school, so more than our cohorts at Brown, we were the ones with the cameras,” she said. “But there wasn’t the self-awareness of today. It was about capturing the rhythm of life, not the pose.”

The pose, in fact, was a lot harder to capture back then, before smartphones, with their filters, cropping features and lighting effects, allowed people to take a dozen of shots of a single moment before fine-tuning a single keeper for public display.

Because film and processing was expensive, students often broke out a cheap point-and-shoot or disposable camera only on special occasions, like parties, when thoughts of formal composition tended to get lost in a haze of Parliament Lights smoke.

“And don’t forget,” Mr. Atkatz said, “you didn’t even know what the damned picture was going to look like for like two weeks. You would snap 24 pictures and then you hope some of them were good. And then you’d get it back and there would be one or two good photos, and a bunch of junk.”

This explains why so many of the shots on the feed are either underexposed, overexposed or framed as if the photographer were blindfolded. But that is the spirit of the enterprise, as well as the era. “That detritus,” Mr. Atkatz said, “is the good stuff.”