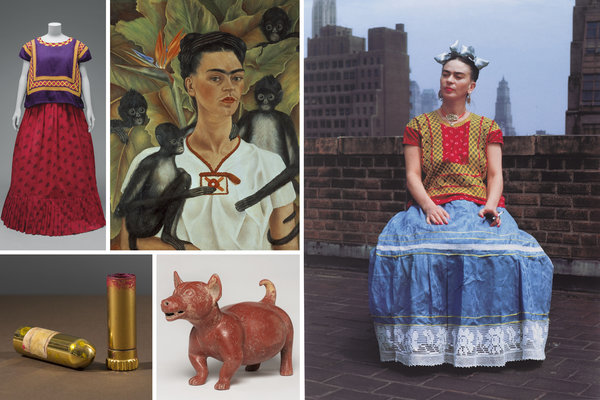

A Tehuana huipil and skirt, with portraits of the artist, in “Frida Kahlo: Appearances Can Be Deceiving” at the Brooklyn Museum.CreditBanco de México Diego Rivera Frida Kahlo Museums Trust, Mexico, D.F./Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Hard to imagine she once worked in shadow; when she had her first New York exhibition, in 1938, Vogue preferred to name her “Madame Diego Rivera.” For there may be no artist today as famous as Frida Kahlo, now recognizable from Oaxaca to Ouagadougou — with those big brown eyes framed by her notched unibrow, those pursed lips topped by a whisper of a mustache. Certainly no woman in art history commands her popular acclaim.

[Read more about how Frida Kahlo meticulously built her own image.]

There is a Frida Barbie. A Frida Snapchat filter (with a suspicious skin-lightening effect). Frida tchotchkes on Etsy and eBay number in the tens of thousands. Beyoncé herself dressed as Kahlo a few years back, trailed by the usual “FLAWLESS” and “SLAY” headlines, and so did more than 1,000 fans who gathered at the Dallas Museum of Art in Frida drag. Even Theresa May, the British prime minister not overly accustomed to celebrating Communists, sported a Frida Kahlo charm bracelet during a major address.

Yet Fridamania, in itself, was not the only reason I went with some apprehension to “Frida Kahlo: Appearances Can Be Deceiving,” which opens this week at the Brooklyn Museum. The show is largely not an exhibition of the Mexican artist’s work, but a recapitulation of her life through her clothing, jewelry and objects from her home. A version of it first appeared at the Victoria and Albert Museum in London, whose most visible recent shows have been lightweight spectacles of celebrity culture. There was every chance, I feared, that this exhibition would follow in the vein of the V&A’s showcases of pop stars like Kylie Minogue, Pink Floyd and David Bowie, the last of which also toured to Brooklyn.

It turns out to be a more rigorous enterprise than those, thanks to the Brooklyn Museum curators Catherine Morris and Lisa Small, who have deepened and broadened the V&A’s version with new loans, surprising films and dozens of pre-Columbian antiquities from the museum’s own collection. (Another good addition: They have written all the wall text and labels in both English and Spanish.) The clothes, lent from Mexico City, are fantastically elegant, above all the rich skirts and blouses from the Oaxacan city of Tehuantepec. As for paintings, there are only 11 here, in a show of more than 350 objects.

More than celebrity relics, Ms. Morris and Ms. Small argue, the clothes are key to Kahlo’s achievement. So are her jewelry and her spine-straightening corsets — Kahlo was in a traffic accident as a teenager, and this show puts a particular focus on her disability. Do her outfits have the weight of art, or are they just so much biographical flimflam? My mileage varied from gallery to gallery, but it’s worth considering, given her admirers’ intense love for her persona, how much can be displaced onto skirts and shawls.

Love for her style has inflated the standing of her art all out of proportion, and in recent decades it’s become an article of faith that Kahlo was a more important painter than her acclaimed husband, indeed one of the indisputable greats. This is — well, not true, sorry! In Brooklyn you’ll find some engrossing self-portraits, including MoMA’s severe “Self-Portrait With Cropped Hair,” but Kahlo also painted half-competent still lifes, gross Stalinist agitprop, and ghastly New Age kitsch — including this show’s “The Love Embrace of the Universe …,” a world-spiritualist tableau featuring a lactating Mother Earth that would make Deepak Chopra blanch. I’d name many other Mexicans, men and women, who drew more productively on surrealist, folk and indigenous vocabularies to force a new art after the revolution, including Rivera, the wily modernist Dr. Atl, the Mexico-based Englishwoman Leonora Carrington and the ripe-for-rediscovery Alice Rahon.

Yet Kahlo was a pioneer in self-disclosure, a national advocate and an essential social connector, brokering introductions between Americans and Europeans and the local avant-garde. She posed constantly for the best photographers, including Tina Modotti, Carl Van Vechten, Imogen Cunningham and Edward Weston. Her real accomplishment, this show proposes, was a Duchampian extension of her art far beyond the easel, into her home, her fashion and her public relationships. Which makes her, for good and ill, a figure right for our time — and also complicates the easy opposition between her Communist convictions and today’s global Frida industry.

Kahlo was born in 1907 in the Coyoacán neighborhood of Mexico City, in a newly built house called the Casa Azul. At 6, she contracted polio. At 18, a trolley car rammed into the bus she was riding; the accident shattered her spine and reduced her right leg to bits. Her father, Guillermo, a photographer who specialized in architectural documentation, took a formal, Europeanized portrait of her a few months after the accident, which appears in the first gallery here. She wears a long, dark silk dress and clasps a book in her hands; her hair is pulled back, her mien is stern. Her right leg, agonizing her, lies half-hidden.

Kahlo’s clothes are the prime draw here, though their splendor is dulled when seen in mirror-backed glass vitrines; in places they look like so many dusty Macy’s mannequins. (Where the V&A show went for visual splash, the Brooklyn version is highly subdued.)

“Appearances Can Be Deceiving” is more interesting as a photography exhibition, whose more than 150 images divulge her meticulous craftsmanship of a stern, self-possessed record for the lens. In studio pictures she appears in full Tehuana dress; no paint-splattered overalls. For Imogen Cunningham she wore a dark cloak and a necklace of chunky pre-Columbian jade.

Manuel Álvarez Bravo, perhaps the greatest of Latin American photographers, made a formal seated portrait in 1938; Kahlo wears her hair in the thick braid favored by Zapotec women, and drapes her shoulders and lap with an intricate rebozo, or woven shawl. Kahlo, like so many metropolitan leftists of Mexico’s post-revolutionary period, romanticized the country’s indigenous population, though she did not see Tehuana clothing as retrograde. A valuable fringed rebozo with interlocking zigzags like the one in the Álvarez Bravo photo was woven from newfangled rayon.

In 1929 she married Rivera, 20 years her senior and one of the most acclaimed modernist painters on the planet, who would receive the second-ever solo show at the Museum of Modern Art in 1931 (right after Matisse). In the painting “Self-Portrait as a Tehuana (Diego on My Mind),” from 1943, her passion for her husband and for her country’s indigenous south fuse into a tacky but strangely compelling icon, which riffs on the 18th-century style of monjas coronadas, or nuns painted as brides of Christ. Diego’s image is tattooed in the chevron of Frida’s unibrow, and framing her face is a stiff lace headdress called a resplandor.

It’s paired here with a photo of Kahlo painting it while Rivera watches, a mannequin wearing her white and pink resplandor, and a wonderful sequence shot from “¡Que Viva México!”, by the couple’s friend Sergei Eisenstein, in which young, beaming women in Tehuantepec fit themselves with the same starched lace ruffs.

Rivera, the bard of lefty Mexicanidad, loved when his young wife dressed in Tehuana clothing; it was a rebuke of the capital’s Paris-envying bourgeoisie. Yet the Brooklyn Museum show proves that Kahlo favored the beautiful ensembles here — striped shawls over white lace blouses, coveralls festooned with woven silk flowers, skirts of canary yellow and rich indigo — for profounder reasons. The long skirts covered her wasted right leg, which was eventually amputated, while the loose blouses also gave breathing room to the corsets and braces she wore to sustain her spine after nearly two dozen operations. A steel brace here, equipped with leather-clad paddles to push back her shoulders, also appears beneath a see-through Tehuana gown in the drawing that gives this show its title: “Appearances Can Be Deceiving.” Orthopedic corsets became canvases in their own right, emblazoned with the hammer and sickle. Even when confined to bed Kahlo dressed to the nines.

The clothes, as well as the corsets and jewelry, were discovered in 2003 in a bathroom at the Casa Azul, where she was born, worked, suffered and died in 1954, age 47. The couple undertook an expansion of the French-style house in the 1940s, ordering an Aztec-inspired extension from Juan O’Gorman (better known for his astounding mosaics at Mexico City’s main university) and decorating it with indigenous stone statuary, papier-mâché figurines, painted gourds and a healthy mix of pets. A rare film here shows the lush gardens that would inspire the dense, Rousseauesque vegetation in this show’s most trademark Kahlo: “Self-Portrait With Monkeys” (1943), featuring a quartet of primates who join the artist in a staring contest.

Countless visitors, perhaps already following her on an Instagram account with nearly a million subscribers, will come to this show because of self-portraits like this one. I hope they also spend time with the even more powerful artworks in the same room: a dozen retablos, or votive paintings on metal by anonymous Mexicans, similar to hundreds of paintings Kahlo lived with in the Casa Azul.

These little devotional works depict sudden violence and racking illness, but also divine intercession; one gives thanks to the Virgin of Talpa for freeing a child from prison, another praises the Holy Trinity for sparing the life of a man crushed by a car. Each is a little masterpiece of suffering and redemption, made with a wrenching, openhearted economy. These artists knew, and Kahlo and Rivera knew when they collected them, that art has a much higher vocation than myth or merchandise.

Frida Kahlo: Appearances Can Be Deceiving

Feb. 8-May 12 at the Brooklyn Museum, 200 Eastern Parkway; 718-638-5000, brooklynmuseum.org.