Style Points is a weekly column about how fashion intersects with the wider world.

When you think of couture, what comes to mind? Parisian confections floating down a runway, most likely. But American designer Ann Lowe’s custom-made designs for social fixtures from Jackie Kennedy to Marjorie Merriweather Post certainly qualify, even if not in the strictest, Chambre Syndicale-approved sense.

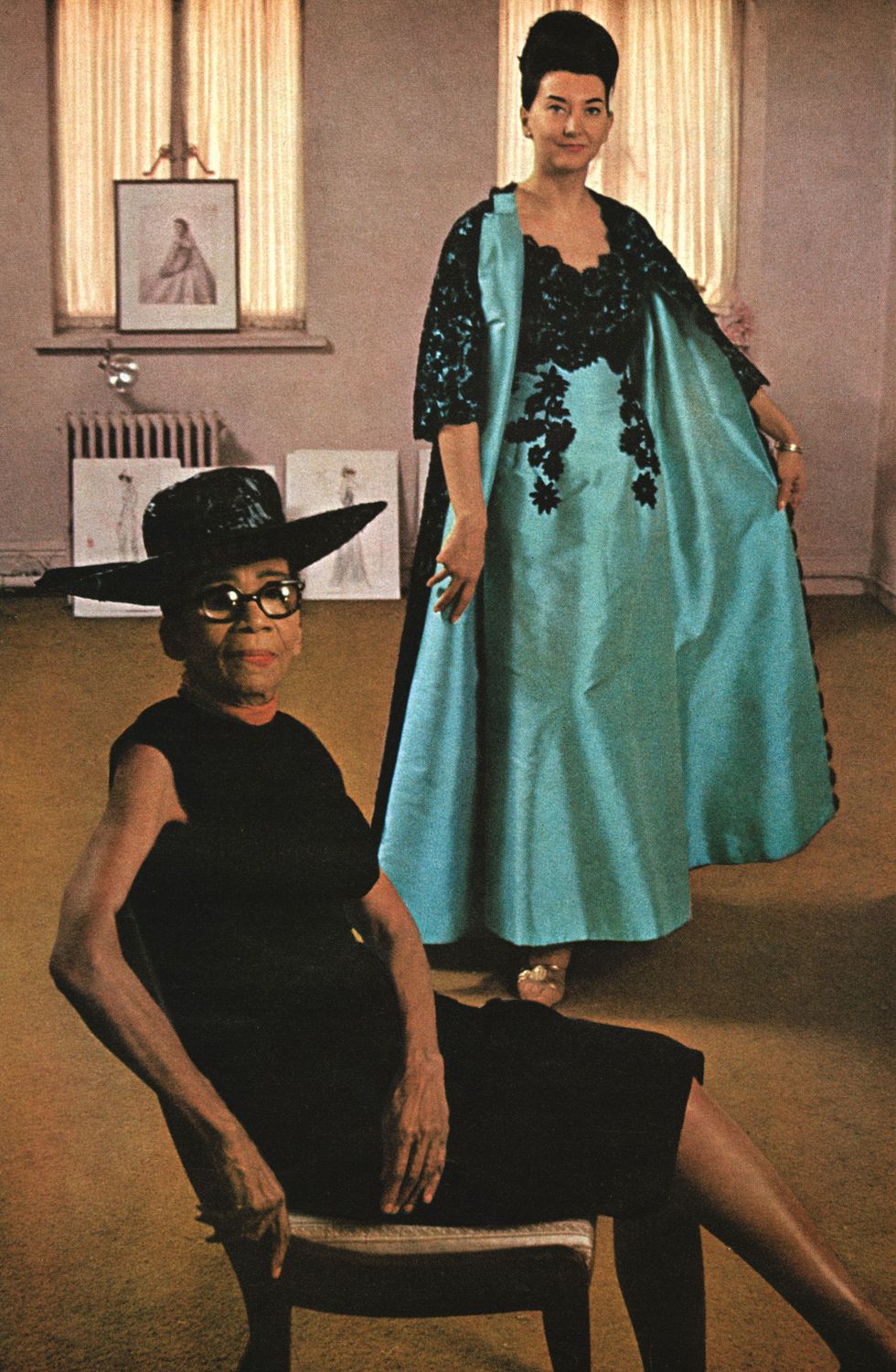

Starting on September 9, Lowe’s historic work will be on display at the Winterthur Museum, Garden & Library in Delaware. “Ann Lowe: American Couturier” was initially the dream project of the late textile historian Margaret Powell, who worked as a cataloguer at the museum. While some retrospectives serve as a rubber stamp on a designer’s legacy, this one is a bit more open-ended. Guest curator Elizabeth Way and her colleagues are hoping that it will alert the public to a designer who deserves to be better known, who battled racism and poverty while designing for midcentury elites, a woman who the Saturday Evening Post once dubbed “Society’s Best-Kept Secret.”

The show might as well be subtitled “CSI: Fashion” for all the detective work it required. There was no official, climate-controlled archive to work from, and not all of her designs have been accounted for. Way, who is the associate curator of costume for the Museum at FIT, tells me that an APB went out for uncatalogued Ann Lowe dresses: “People would reach out to us and say, ‘I have a picture, I have a dress, I have a story.’” Not to mention that re-creating one of Lowe’s most famous creations (more on that in a moment) involved retracing her stitches, Sherlock Holmes-style.

Lowe grew up in turn-of-the-century Alabama, learning dressmaking from her grandmother, who had been enslaved. “Her grandmother and mother gained their freedom when her grandfather purchased it,” Way says. They went on to design for notables, including the First Lady of the state. “They’re working in the Jim Crow South, building up a business that is serving an elite white clientele. And this is at a period when most Black women were working in sharecropping or as domestic servants. They were doing relatively clean, safe work that was a creative outlet, and they were business owners. Dressmaking was some of the highest-paid, most respectable work that women, Black or white, in the 19th century could engage in. So it was really remarkable, as Black women, that they were able to take this accepted road of occupation, but turn it into something that they could pass down, and use it to sustain themselves.”

When Lowe moved to New York to enroll at S. T. Taylor Design School in 1917, the administration “didn’t actually know that she was Black until she showed up on the first day. And to appease the majority white people in this institution, she was seated off in another classroom. But quite quickly, because she was doing such great work, her teacher would take her work and bring it in to the other students,” says Way. “Before she knew it, they were hovering at the door, looking at what she was doing. And she graduated in half the time. She had been training as a dressmaker since she was a child, so it’s not surprising that she had these advanced skills. But I think one of the ways she dealt with discrimination was by being the best. That was how she dealt with the obstacles that were put up in front of her.”

Lowe began designing for socialites, including famous families like the Rockefellers and DuPonts. Alexandra Deutsch, the museum’s Director of Collections, notes that her “meticulous handwork and sculptural fabric flowers…made her gowns instantly recognizable status symbols for society women.” That power resonated well beyond the Blue Book. “A typical woman might see a dress on a DuPont and say, ‘I want my wedding dress to be a little bit like that,’” Way says. Lowe was proud of her connections to high society, telling Ebony: “I do not cater to Mary and Sue. I sew for the families of the Social Register.”

Way compares Lowe’s story to that of Mary Todd Lincoln’s dressmaker Elizabeth Keckley, “who had been enslaved and had bought her freedom through her dressmaking work, but was a socialite within Black Washington, D.C. She did derive status from her association with these elite white people. And I think Ann Lowe looked at it in much the same way. Her work was appreciated by them, and she didn’t receive a lot of press from it. But I also think that that was kind of the nature of the beast at that time, to design for this level of people. There was an expectation that you weren’t publicizing it; you were keeping it discreet.”

Lowe took pride in her association with boldface-named socialites, but it didn’t always show her the same veneration. She is perhaps best known for being the designer of Jacqueline Kennedy’s wedding dress, but she wasn’t credited as such at the time. “In Ladies’ Home Journal, she was referred to as ‘a colored woman dressmaker,’” Way says. “I think that did really bother her. She wrote to Jacqueline Kennedy’s press secretary, expressing that she was very displeased. The press secretary wrote back and said that Mrs. Kennedy had not approved those quotes, that that was not a direct quote from Mrs. Kennedy, and they apologized.”

For the show, which features over 40 Lowe pieces, Kennedy’s gown needed to be recreated, since, explains Kim Collison, the museum’s curator of exhibitions, it was too fragile to travel. Katya Roelse, an instructor at the University of Delaware’s fashion department, took on the challenge, working with the museum’s conservation staff on research and a group of students on construction. Way estimates that it took around six months: “everything from sourcing the right materials to recreating the pattern…it was [like] living with Ann Lowe in that time, going through, looking at the stitching, looking at the way things were put together. [Roelse] said that you could tell where Lowe was kind of rushing the process, because, of course, it had to be remade; the first version was ruined in a flood in her workshop. But Lowe knew where she could take some shortcuts, and where she needed to take her time. You really saw her experience wrapped up in that dress.” The recreation will have a new home at the Kennedy Library after the show.

In her later life, Lowe struggled with both health and finances. “I didn’t realize until too late that on dresses I was getting $300 for, I put about $450 into it,” she told the Saturday Evening Post. She suspected that Kennedy might have been the anonymous benefactor who stepped in to pay some of her debts after she filed for bankruptcy in the 1960s.

The exhibit also includes the work of contemporary Black designers like Tracy Reese and Dapper Dan who are influenced by Lowe and, Deutsch says, have a “deep appreciation for her determination and a great sense of pride in her accomplishments. Her legacy and the challenges she faced throughout her career mirror some of the challenges Black fashion designers still face today.”

As for whether the exhibit will hit the proverbial road like so many fashion exhibitions before it, Way says, “It certainly has come up, and we were very excited at the prospect, but unfortunately, the gowns are quite fragile, and we don’t want to keep them on display for too long. So at this point, we don’t have travel plans, but there is a lot of material culture out there, so even if it happens in a different iteration, with a different institution, I do hope that her material culture continues to be displayed.”

And, as a bonus, it might succeed in unearthing more of her designs. Says Collison, “We hope people who attend the exhibition and see Lowe’s work will perhaps recognize something long-forgotten that is hidden away in the back of their closet.” If so, she hopes “they let us know about it.”

ELLE Fashion Features Director

Véronique Hyland is ELLE’s Fashion Features Director and the author of the book Dress Code, which was selected as one of The New Yorker’s Best Books of the Year. Her writing has previously appeared in The New York Times Magazine, The New Yorker, W, New York magazine, Harper’s Bazaar, and Condé Nast Traveler.