A mayor really isn’t supposed to say something like this.

“We don’t want tourists.”

I waited for the punch line. None came.

“We don’t want to be occupied by tourists,” he continued.

Tourism, he explained, will deplete a city of its soul — and this city has a prehistoric soul.

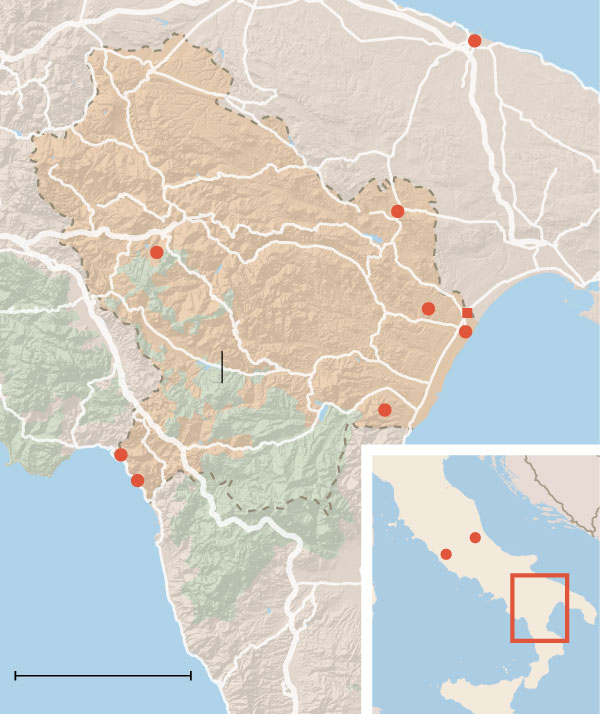

I was in Matera, an ancient city of about 60,000 people, perched on top of Italy’s high heel. Mayor Raffaello De Ruggieri and I sat under a pergola of young vines, a spotty veil of shade beneath the Mediterranean’s punishing sun. In 2019, Matera — the jewel of the southern Italian region of Basilicata — will be anointed the European Capital of Culture. It is a source of great honor and pride for the town. All year long, there will be festivals and exhibitions. Thousands upon thousands of, well, tourists will descend on the city.

“This city has been alive for 8,000 years,” he told me. “But it has always been poor.”

Mr. De Ruggieri then began to review those last 8,000 years. And as he did, three dates in Basilicata’s recent history appeared over and over: Nineteen-thirty-two, when Basilicata was renamed Lucania by the Fascists (it reverted back to Basilicata in 1948). Nineteen-forty-five, when the dissident doctor and writer Carlo Levi published his memoir of exile here, “Christ Stopped at Eboli,” which became a definitive document of the realities of Southern Italy — extreme poverty, famine, disease, widespread malaria. Finally, 1993, and redemption, when the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization, or Unesco, added Matera to one of the most exclusive lists in the world.

Mr. De Ruggieri eyes crinkled with pride at the last development. “We went from shame to being a World Heritage site,” he said.

We were on the patio at the Sextantio Le Grotte Della Civita hotel having coffee and overlooking a ravine — a steep, rocky valley leading down to a gurgling riverbed and the dark, ancient, caves of Parco Nazionale Alta Murgia. Around us, the city told its own history: crude stone walls, stairs worn by armies of time, and, most extraordinarily, Paleolithic caves, once home to families and farm animals, carved into the matrix of the town. Some of them had recently, symbolically, been repurposed into luxury hotels and cafes. It was a striking dichotomy: A view that will transport you to the ancient past and a caffè macchiato that will bring you right back to the five-star present.

As recently as the 1950s, more than 15,000 people lived in the caves, but in 1952, the authorities declared that the living conditions in the caves were unacceptable and living in a cave became illegal. It wasn’t until 1986 that the Italian government realized their value and invested money in the rehabilitation of the caves.

“There are two sisters who have lived in a cave since 1950,” the mayor told me, conspiratorially. “They never left.”

I had only been in Basilicata for a few days, but I’d already come to understand that this region has quirks. This is not like the rest of Italy. First of all, Basilicata makes you work for it. This misshapen, green, rocky, mountainous piece of land stretches to two coasts and comprises the awkward instep of Italy’s boot. And there is no easy way in. There are no airports, no high-speed trains from Rome (or anywhere else). There are no major cities or world-famous destinations. The roads are narrow and curled like fusilli. In Basilicata, it takes a long time to go anywhere. If you’ve made the journey in, any plans to rush out are futile. You’ve come to stay, which really isn’t such a bad thing.

The village of Pignola, tucked into a hilltop, is pure Italian charm.CreditSusan Wright for The New York Times

Plans, and braking for pastas

Two friends had come with me — Raffaele, a local, from Southern Italy; and Lisa, a nonlocal, from Southern California. Our plan was to make a beeline from the airport in Bari to the western flank of Basilicata, then work our way eastward: From the town of Sapri on the Tyrrhenian coast, through the hills of the Campania border, wending along the Ionian coast to the southern edge of Basilicata, and finally to Matera, the gnarled crown jewel, where we would come to our journey’s end.

But plans change. We got hungry.

On our drive to Sapri, we hit Pignola. Tucked into a hilltop, Pignola is pure Italian charm: crumbing stone buildings and narrow, unnavigable streets. We could almost hear the sizzle of the olive oil and the crunch of the local dried peppers, peperoni cruschi. We parked our tiny toy rental car, which may or may not have been made of actual Legos, unfolded our limbs, and strolled toward centro.

But this is Mezzogiorno, the south of Italy, and entire postal codes can close for no apparent reason. Including, apparently, every restaurant in town.

A woman in a housedress and Elvis sunglasses directed us a few minutes outside Pignola where we found the Ristorante Pizzeria Le Fiamme. It sits perched on a hill — Basilicata’s endless greenery unfurling before us.

We sank into our wine and pasta. The wine was . . . wine. A local white. But the pasta. Imagine squares of dough folded into tubes by a lazy second grader then flattened. This is strascinati. And this strascinati was tossed with bread crumbs, fresh parsley, tomato sauce and glistened with olive oil — served in a neat dome with the crushed dried peppers on top. It was so simple — crunchy, chewy, sweet, savory, perfect in every way. Strascinati mollica e peperoni cruschi is cacio e pepe without a marketing campaign.

Leaving the restaurant, I learned the best way to see Basilicata: Supine in the back seat of a Lego car, propped up on my friends’ jackets, gazing at the green mountains and blue sky in a dreamy, fatigued strascinati haze. It was a screen saver of a view.

We headed westward to the side of thunderous green mountains, on serpentine roads as monstrous wind turbines — pinwheels of the gods — churned slowly on the horizon. Curiously, this was also the side of no humans. Lisa, Raffaele, and I drove for hours through the Parco Nazionale dell’Appennino Lucano Val d’Agri, passing three, maybe four, other cars.

It’s unsettling to move through such a vast, beautiful landscape and feel so alone. It’s what the world would look like if people were gone and Mother Nature redecorated — carpeting hills with waist high grass and sprinkling them with zealous yellow flowers. Ginestra, Raffaele explained.

It’s a landscape that can make it easy to forget the hardship Basilicata has endured. This part of Italy has been conquered and conquered again (by Byzantines, Ostrogoths, Arabs, Greeks, Spaniards, the list goes on). Even today, it suffers from a declining population and unemployment higher than the rest of Italy’s — which is high to begin with. The remoteness of the region is what makes it so special but doesn’t necessarily entice younger generations to plant roots or build industry here.

[Get weekly updates from our Travel Dispatch newsletter, with tips on traveling smarter, destination coverage and photos from all over the world.]

To one coast, and then the other

Tell people that you are going to Maratea, and they will correct you. “Matera, you mean,” said more than one Italian friend. Stand your ground. “No,” you must insist. “Maratea.”

Maratea, a small, coastal town, is perched just above the Tyrrhenian Sea — mountainous and lush, with dramatic black sand beaches. You almost feel like you could be in Hawaii, but the town itself is pure Mediterranean. When we arrived, we ditched the car and walked the shopping area — the pedestrian-only streets made of white stones that are somehow more blinding than the sun. Maratea is for strolling, stopping for an aperitivo, taking in a view.

The next morning, we headed to the beach — an impressive landscape of imposing cliffs, black sand, and a curious juxtaposition of cedar trees next to electric blue Mediterranean waters. It was a chilly morning and the sea was churning up white caps. We had no plans to swim but in case we had, the name had already talked us out of it: Spiaggia Acquafredda. The Beach of Cold Water.

But the warmer Ionian Sea is only a few hours away. A short while later, we were on our way — the landscape changing from lush and verdant to dry and rocky. Head east long enough and Basilicata becomes the color of dust and ancient ruins.

We arrived at the Tavole Palatine, 6th century B.C. Greek ruins dedicated to Hera in the town of Metaponto by early afternoon. Imagine long rows of connected limestone columns framed by bushes of oleander — pink and white flowers that are fragrant, delicate and deadly. No one was there, not a soul. It felt more like being in the backyard of an eccentric billionaire with a green thumb than an ancient temple to the Greek goddess of marriage.

Just inland from the ruins is the town of Bernalda, and Francis Ford Coppola’s hotel, Palazzo Margherita. Chances are, if you have ever heard of a hotel in Basilicata, it is this one — a 19th-century palazzo Mr. Coppola converted into a nine-room luxury hotel in 2004.

“Every 10 kilometers, it changes, Basilicata,” said Rossella De Filippo, the hotel’s manager. “Different skyline, different colors, different everything. This is what makes Basilicata special.”

We had met Ms. De Filippo in the Cinecittà Bar at the Margherita. I have spent time in Puglia, Calabria and Sicily — but Basilicata is different, calmer. I asked Ms. De Filippo, who grew up nearby, why Basilicata is quieter than the surrounding regions.

“We like say that we are so poor that even the mafia isn’t interested in us,” she said, wryly. You can only be in southern Italy for so long before the subject comes up — the oppressiveness that hangs over everything like a low cloud cover that never burns off. Sicily and the Cosa Nostra. Calabria, which shares a border with Basilicata, and the ’ndrangheta, arguably the most violent organized crime group in Italy. But Basilicata, smack in the middle of southern Italy, has no major criminal element.

“The real Lucani are poor, naïve maybe, but they are kind,” said Ms. De Filippo, using the region’s alternate name. “Farmers, shepherds, they are not people that the mafia is interested in. They are simple, but incredibly generous.”

They were prescient words.

Onward to Matera

When we got back in the Legomobile, we called a man named Daniele Kihlgren, the owner of Sextantio Le Grotte Della Civita, easily the most luxurious hotel in Matera. Mr. Kihlgren is largely credited with advancing the albergo diffuso movement in Italy. It champions the idea that disparate structures, as opposed to a single, monolithic building, can comprise a hotel. Albergo diffuso, diffused hotel, has played a big role in preserving ancient towns and structures. By all accounts, Mr. Kihlgren is a conservationist, a man of impeccable taste, and something of a character.

We reached him as he was driving north by motorcycle to his other hotel in Abruzzo. (We had scheduled an interview a few days earlier, but things come up, especially in Italy.) No worries, he would happy to turn around, he said. What about the storm coming in? We asked. He wasn’t worried.

By evening, torrential rain had turned biblical, as Mr. Kihlgren drove his motorcycle to meet us for dinner. Rivers of rainwater coursed down the steps and streets of Matera, power-washing the city, cleansing it of anything that wasn’t millennia-old.

The four of us sloshed into the caves of Ristorante La Talpa.

There are meals so gluttonous, so meaningful, so caloric, that they imprint themselves on your personal history. Dinner at La Talpa was such a meal.

There were fried artichokes, bread salads with bright vegetables and salty, local cheese; there was a covered pizza, skinny and gooey with smoked mozzarella and spinach; crostini con cicoria e purè di fave, crostini with chicory and fava bean purée (a local specialty); there were breaded meatballs; there were sage leaves the size of a child’s shovel, fried, salty and crispy. There was more, so much more, but the plates came out of the kitchen faster than I could eat what was on them.

“Tourism screws up the identity of a place,” said Mr. Kihlgren, stroking his goatee. “The only way to solve this contradiction is to make sure you are obsessive about the identity of the place.”

People in the hospitality industry reliably talk about the importance of authenticity. For Mr. Kihlgren, it is religion.

“Once you clean it too much, you lose the character. You lose the soul of the house, the souls of the people who lived there,” he said. “These are ancient historical nests — they should provoke an emotion. They are not supposed to be beautiful.”

We paused. The verdure pastellate, battered and fried vegetables, arrived along with still more delicious, if unidentifiable, crostini.

“When I bought the hotel, the caves were black,” he continued. “We had to clean it, but we didn’t want to clean it too much. The poor, historical villages of Italy were never thought to be worthy of saving. But to preserve the history is very important. There are 2,000 abandoned villages in Italy. We are not competitive with Silicon Valley or the mass production in China but we are rich in this history. It could be a model for us: to preserve our heritage.”

He sampled the antipasti. Then he added, “Fifty years ago, people here were dying of malaria, and now we are at 80 percent occupancy,” he shook his head. “I feel ashamed of this.”

It was now close to midnight, there was nothing left to eat. It was time to go to the hotel.

I have toured the stalactites in Quintana Roo with my children. I have sampled blue cheese aging next to bats in natural underground vaults in rural Spain. But I have never actually slept in a cave. And I can now say that it is a wonder early man ever evolved.

A cave, I learned, is a potent, prehistoric Ambien. The deep black, the cool air — ‘sleep’ is a mild word for the slumber you fall into. I woke up 11 (11!) hours later, candles still flickering, dutifully standing watch from their stony nooks, only the tiniest splinters of sunlight poking in from under the door.

I had coffee with the mayor, and soon we were joined by Salvatore Adduce, President of the Matera Basilicata 2019 Foundation.

“I will be brutal: We do not want tourists,” said Mr. Adduce, an avuncular gentleman in a crisp shirt and thickly knotted tie. “It should not be, ‘Let’s see a church and eat pasta and try those crunchy red peppers and leave a few pieces of plastic behind.’”

I sank in shame. I disposed of my recycling properly, but the truth is, I had grown quite fond of the crunchy red peppers.

“I want people to have an experience that will change their lives, change the world,” he said. “For the exhibitions next year, Matera will sell passes — 19 euros, good for one year. The visitors will be temporary cultural inhabitants, and they will be asked to leave a personal item behind. At the end of the year, these items will become their own exhibition.”

This is the only region of Italy that has an alter ego, the only one that goes by two names. Depending on your age and generation, it is either Lucania or Basilicata, with a painful past and a glittering future as the European capital of culture.

On our last day in Matera, we met old friends for lunch. My friend Francesco is from a small coastal town called Nova Siri, but he and his husband, David, currently live in Puglia.

“You have to remember, I ran away to Rome when I was 18, and I didn’t come back for five years,” Francesco said. “I told people I was from Basilicata, and they didn’t know what it was. Actual Italians didn’t know Basilicata. They would say, ‘That’s in Sicily, right?’”

Fran has dark, Mediterranean skin, a joyful, handsome face that belies his years, and wears small silver hoops in his ears. He’s one of those people who can’t stop smiling for long. We met at one of his favorite spots, not far from the Conservatorio di Matera where he studied piano for five years.

A waiter arrived at the table, placing a bowl right in the middle. It was a soupy dip of warm fava beans, chickpeas, olive oil and onions.

“This is the food of my childhood,” Fran said. “The beans have to soak for days, you keep cleaning the water and adding herbs. I remember people would think, ‘Lucani are so poor they can’t afford meat.’ But I loved this food. It’s simple, like the Lucani.”

Around us, there was construction for exhibitions going up in 2019, platforms that would become a world stage.

“Basilicata is a hard but beautiful life,” Fran said, taking on an uncharacteristically serious tone. “One side of me thinks it’s important for the world to discover it. The other side knows the Lucani don’t want a connection with the rest of the world.”

It was unlike him, this somber reverence. But soon the moment passed.

“I guess we have to wait and see,” he paused. “Let’s eat!”

Danielle Pergament is editor in chief at Goop.

Follow NY Times Travel on Twitter, Instagram and Facebook. Get weekly updates from our Travel Dispatch newsletter, with tips on traveling smarter, destination coverage and photos from all over the world.