This is a crypto coin. Like a real coin, it is a representation of value. Unlike a real coin, you can’t hold it.

To help you relate, we have anthropomorphized it.

This coin’s every movement — and the movement of every coin like it — is recorded in a constantly updating, shared ledger.

That ledger is called a blockchain! Ever heard of it?

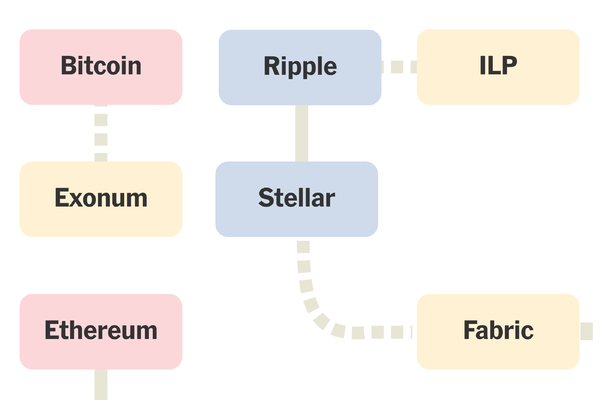

People are very excited about using blockchains. Mostly for making money. Bitcoin was first! Then came Ethereum!

But a constantly updating ledger can have other purposes. It can be good for contracts! And tracking where food comes from!

Perhaps it will save journalism, too?

Hype around the technology has led to incomprehensible applications of it.

Civil Media Company was introduced earlier this year as both a media platform and a network, to be owned and operated by journalists and concerned citizens in tandem. It was an exciting proposal. Its technology (powered by the blockchain!) would churn under dozens of independent newsrooms, its machinery creating a new, utopian model, free from the clutches of miserly businessmen or politically-compromised publishers threatening to gum up the works.

“We believe that the ad-driven business model is slowly killing good journalism — which is itself a critical foundation for free, democratic societies,” wrote one of the company’s founders, Matt Coolidge, in one of many, many, many blog posts that have been written trying to explain Civil. “So, we’re introducing a new model.”

Fundamental to the model was an option for readers: They could buy into Civil, with a Civil-specific crypto token, which would somehow free journalists to take advantage of “self-governance” and “permanence,” Mr. Coolidge wrote. With this financing, Civil would be able to cut out advertisers, clickbaiters and all the other bad actors so often accused of screwing up journalism.

Civil took its currency to market in September for a month. In the end, it fell short of the minimum number of tokens it had hoped to sell by more than six million dollars. Of the approximately $1.4 million worth of tokens the company did sell, about 80 percent was purchased by ConsenSys — the blockchain software company that underwrote Civil in the first place. It was as if an Olympic weight lifter said that, at a minimum, he’d be able to clean and jerk 400 pounds, and then did not manage to move the bar more than an inch off the ground.

The Solution

Civil’s representatives said they could help fix two crises that afflict the media: one of trust and another of financial sustainability. Both, they posited, were within the power of the blockchain to heal.

Financial sustainability first: Civil’s newsrooms (18 listed on its site so far) are welcome to use traditional business models (like subscriptions, paid for with dollars), and many, like the Colorado Sun, Block Club Chicago and Popula, an “alt-daily” with a worldly mind-set, have chosen to do so. But as citizens became convinced of Civil’s value as a publishing platform, they could opt in to the network by purchasing Civil tokens. These would buy them some control, making them, essentially, shareholders. They could “tip” journalists with tokens or portions of tokens, request stories or even suggest the creation of whole newsrooms dedicated to specific subjects. As the news organizations got stronger and stronger — ostensibly, with the input of citizen-shareholder-readers — others would purchase tokens, the value of the tokens would increase, and the entire community, journalists and readers alike, would prosper.

At the same time, Civil representatives said, the much-lamented if near-perennial and also possibly invented problem of trust in journalism would be solved by the blockchain technology’s inherent function as a database.

Vivian Schiller, a former president and chief executive at NPR and head of news at Twitter, is now the chief executive of the Civil Media Foundation, the organization in charge of “upholding the principles of the network.” She wrote, in a blog post, that Civil websites would have an icon in their upper right hand corner that would function as a journalistic equivalent of the “Good Housekeeping seal of approval.”

“We have a plug-in that allows you to sign your work,” said Mathew Iles, the chief executive of the Civil Media Company, which is separate but related to the foundation. “This is important: We’re going to be able to show citizens that you in fact did write it.”

To be clear, the crisis of faith in media did not spring from confusion regarding the disputed identity of authors of blog posts. This was one of several examples in which Civil suggested that if the concerns of journalists themselves (about interference from publishers, or the sudden erasure of digital archives) were taken care of, the broader problem of trust in the media would be eased.

“Do we think that by launching Civil, somebody that thinks that the press is the enemy of the people, are those people suddenly going to go ‘oh I see the light’? Of course not,” Ms. Schiller said, before the token sale began. “But here’s what we can do: If Civil is successful, it will allow people who are interested in trustworthy journalism, it will be a signal to them for what news organizations meet the criteria.”

Oh, and, Civil would also become a social network, one that would thwart the power of the big technology companies. Mr. Iles said he had spent years watching Google and Facebook manipulate and take advantage of their media partners. “The first time that I really started conceiving of Civil, I viewed it as an open publishing platform that had to be decentralized,” he said. “Social media with rules.”

So it would be like Facebook, but journalism, but on the blockchain?

“All cryptoeconomic public blockchains are effectively social applications,” Mr. Iles said. “You need a crowd of people to agree to run it.”

So: Civil is a media company that supports but also is a group of linked newsrooms that is also a blockchain-based social network which is supported by tokens that are purchased by people who care about journalism.

Wait. What?

The Problem

The technology that undergirds cryptocurrency is complex, but because it’s been touted as the next big thing for the last several years — teenagers have Coinbase Wallets and various semi-normal people got rich quick with Bitcoin and then poor quicker — it feels as if even the less financially-sophisticated of us should have wrapped our heads around the whole phenomenon.

People who are in a strong position to understand what Civil is doing — either because they are experts on blockchain technology or because they work for one of its newsrooms — have openly admitted that they don’t understand how the organization works. The rate of such statements only increased as Civil’s token sale got underway in September.

The collective confusion might have something to do with how the Civil token (called a CVL) is meant to work.

“People who want to buy CVL tokens are token buyers, not investors,” Mr. Iles said this summer. “The consumer token is critical to us because what we are essentially doing for the person is deploying a cryptocurrency that is primarily about using it to operate a network.”

In essence, that means: Buying CVL isn’t meant to make you money.

Cryptocurrencies like Bitcoin (which introduced blockchain technology to the world) and Ethereum are commodities — like gold, they fluctuate in value whether they are used or not. CVL tokens were designed to function as consumer items. In practice that means that Bitcoin and Ethereum have tempted even know-nothings to make a purchase in the hopes of getting rich quick. Civil is asking people to buy in for the privilege of enthusiastically participating in running a blockchain-media platform.

Or, as Mr. Iles put it: “We even think that we are going to be able to show people that it’s more fun, it’s more rewarding, to pay for the news using CVL tokens as opposed to cash.”

But many people aren’t willing to pay normal money for journalism.

“Look, we sometimes get asked, are we too early?” Mr. Iles said. “And the answer is absolutely yes. But you only are ever going to be too early or too late.”

Fewer than three thousand people were willing to buy tokens. The sale certainly suffered from how complicated the buying process turned out to be. John Keefe, a writer at Quartz who wanted to invest in the project, described his experience in an article for Nieman Lab, “How to buy into journalism’s blockchain future (in only 44 steps).”

Catherine Tucker, an MIT economist who has paid close attention to the rise of blockchain said that she thought Civil had a targeting issue.

“Ultimately the ideal customer is someone who knows enough about crypto to get through the token-buying test and cares enough about journalism to not mind that the token is restricted in its use,” she said. “I suspect that it is a small intersection of the population.”

What Now?

Journalists running Civil newsrooms continue to express belief in the company. Larry Ryckman, the editor of the Colorado Sun, expressed his faith and optimism in Civil several times in conversation a few days after the token sale failed in mid-October.

At the same time, he said, “We at the Colorado Sun have never counted on the tokens being worth anything necessarily. We were paid in dollars and our readers interact with us in dollars.”

At least one former employee believes that Civil was never built to succeed in the first place. Daniel Sieberg, one of the company’s co-founders, who left in July, said that the token was fatally flawed.

“It is fundamentally a locked box,” he said. “The token’s not worth anything. The simple fact is, the token isn’t necessary.”

During the waning days of the sale, Mr. Iles said he did not feel chastened. He remained bullish about Civil’s future. He said that he felt the token sale had been a misstep, because the organization had set an arbitrary value on the token. Most importantly, he said, the company had failed to explain itself clearly.

“To me this is a big so what, frankly,” he said of the sale’s then-imminent failure. “Just because we’ve potentially set a price that was higher than the market was willing to bear right now is not a referendum on whether or not we’re ever going to reach critical mass. It just means we potentially overshot now.”

It is still unclear how Civil plans to alleviate people’s confusion in order to achieve its mission. But the company is retrenching, thanks to an additional $3.5 million in funding from its original investor, the blockchain software company ConsenSys. (Civil will also offer refunds to frustrated individuals who want to return their tokens.) A new token sale is in the works, though details have not yet been released.

Still, a problem remains: People don’t buy into blockchain applications unless they can make money. There is no evidence that people want to use it to “fix” journalism. There is also no evidence that anyone really understands how that would even work.

For now, Civil is essentially just another media operation with venture capital funding. The money underwriting it, from ConsenSys, remains, you know, regular money. The company uses some blockchain technology underneath the hood, including a plugin for its publishing software. But the technology remains difficult to comprehend, and, for any news consumer’s purpose, irrelevant.

CreditIllustrations by Tracy Ma/The New York Times