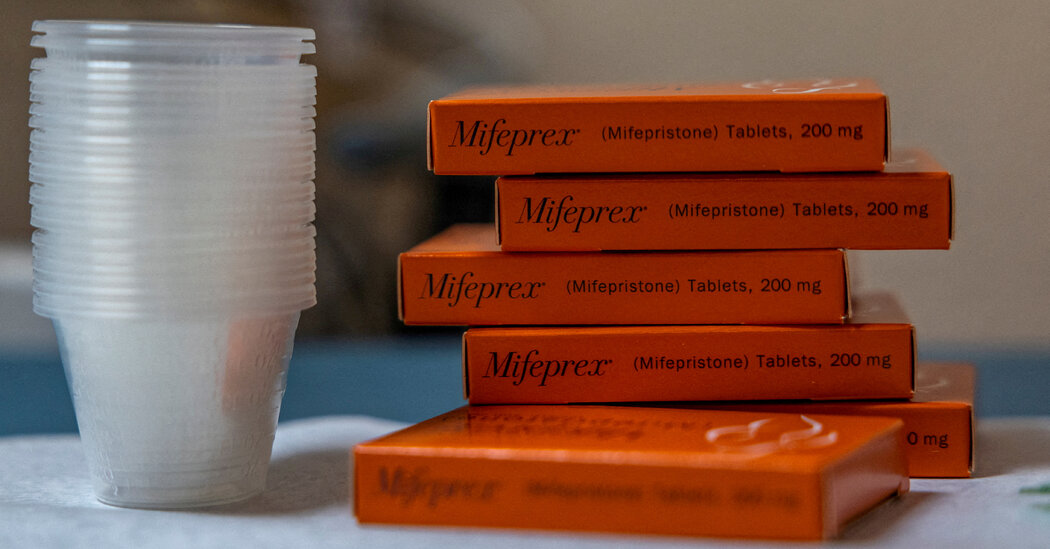

A federal judge’s ruling to revoke the Food and Drug Administration’s longstanding approval of the abortion pill mifepristone poses threats to the U.S. government’s regulatory authority that could go far beyond one drug, legal experts say.

The decision by a Texas judge appears to be the first time a court has moved toward ordering removal of an approved drug from the market over the objection of the F.D.A.

If the initial ruling, a preliminary injunction issued on Friday, withstood appeals, it could open the door to lawsuits to contest approvals or regulatory decisions related to other medications. And if upheld, the Texas decision would shake the very framework of the pharmaceutical industry’s reliance on the F.D.A.’s pathways for developing new drugs, legal experts said.

“This is a frontal assault on the legitimacy of the F.D.A. and their discretion to make science-based decisions and gold standard approval processes,” said Lawrence O. Gostin, director of the O’Neill Institute for National and Global Health Law at Georgetown University. “It ultimately takes us on an extraordinarily dangerous path for F.D.A. as an agency, and for science-based public health decision-making more broadly.”

Congress gave the F.D.A. overarching authority to determine whether drugs are safe and effective in the Food, Drug and Cosmetic Act of 1938. Drug companies must conduct a series of animal studies and human clinical trials that can take years and millions of dollars to provide enough evidence to the agency that a drug is a safe and effective treatment for a disease or a medical condition.

For nearly a century, courts have usually deferred to the federal agency’s scientific expertise and oversight. Yet the use and approval of a wide array of medications have increasingly become the focus of political rifts and state-level disputes over such disparate issues as the opioid crisis, Covid vaccines and gender-related treatments.

Now, the ruling in the Texas case — and a contradictory ruling the same day by another federal judge in a separate case in Washington State — have thrust the issue of F.D.A. authority into the spotlight as never before, and the issue is almost certain to land before the Supreme Court.

“If this ruling were to stand, then there will be virtually no prescription, approved by the F.D.A., that would be safe from these kinds of political, ideological attacks,” President Biden said in a statement on Friday night about the Texas decision.

The powerful pharmaceutical industry has not officially weighed in on the Texas ruling, or indicated whether it will file briefs in support of the F.D.A. In a statement, Priscilla VanderVeer, vice president of public affairs for the Pharmaceutical Research and Manufacturers of America, or PhRMA, echoed others in referring to the F.D.A. as the gold standard for drug approvals.

“While PhRMA and our members are not a party to this litigation, our focus is on ensuring a policy environment that supports the agency’s ability to regulate and provides access to F.D.A.-approved medicines,” Ms. VanderVeer said.

Understand the U.S. Supreme Court’s Term

Mifepristone is the first pill in the two-drug medication abortion regimen. The plaintiffs in the Texas lawsuit are also targeting the second drug, misoprostol, which is approved for other medical conditions but used off-label for abortion. A spokeswoman for Pfizer, which makes a small percentage of the misoprostol sold in the United States, said it did not support off-label use of any of its medicines and declined to comment about whether the company would submit a court brief supporting the F.D.A.

But, she said that “the agency serves a critical role in the U.S. public health system — bringing new medicines to patients and conducting ongoing safety reviews that support the continued use of them — that must be maintained.”

In the Texas case, which was filed by a consortium of anti-abortion groups, the judge, Matthew J. Kacsmaryk of the U.S. District Court for the Northern District of Texas, declared the F.D.A.’s approval of mifepristone in 2000 to be invalid. Judge Kacsmaryk, who has longstanding affiliations with conservative Christian organizations and has written critically of Roe v. Wade, stayed his injunction for seven days to allow the F.D.A. to appeal to a higher court. So, for now, mifepristone remains available.

In the Washington State case, Democratic attorneys general from 17 states and the District of Columbia challenged extra restrictions that the F.D.A. imposes on mifepristone. In a preliminary injunction, Judge Thomas O. Rice of the U.S. District Court for the Eastern District of Washington, ordered the F.D.A. not to limit the drug’s availability in those jurisdictions, which make up a majority of the states where abortion remains legal.

The Justice Department, which is representing the F.D.A., immediately said it would appeal the Texas injunction to the Fifth Circuit Court of Appeals.

In response to the Texas ruling, the F.D.A. said its “approval was based on the best available science and done in accordance with the laws that govern our work.”

The agency added, “F.D.A. stands behind its determination that mifepristone is safe and effective under its approved conditions of use for medical termination of early pregnancy, and believes patients should have access to F.D.A.-approved medications.”

R. Alta Charo, a professor emerita of law and bioethics at the University of Wisconsin and an author of a brief by drug-policy scholars in support of the F.D.A., said, “The biggest threat that a decision like this brings is the threat of creating chaos.” The ruling, she added, could empower a range of groups to begin “looking over the shoulder of the F.D.A., re-evaluating their risk-benefit analyses.”

The agency has faced a series of reputational broadsides in recent years. Under President Donald J. Trump, the F.D.A. was maligned for bowing to political pressure to authorize Covid treatments that turned out not to be helpful. It faced searing criticism over its approval of Aduhelm, a controversial Alzheimer’s drug with uncertain benefits and significant safety risks. And it continues to face the wrath of the public and lawmakers who question several opioid drug approvals granted amid rising overdose deaths.

Some experts in reproductive health law and drug policy say that, while the Supreme Court decision overturning Roe v. Wade allowed each state to decide whether to ban or permit abortion, it did not allow states to take actions to bar the medications used in abortion, because those are regulated by the F.D.A. States are allowed to adopt some laws and regulations that supplement federal rules on drugs and to regulate the practice of medicine within their jurisdiction. But states cannot impose policies that interfere with or contradict F.D.A. standards or requirements, so they cannot ban or drastically restrict a medication the federal government has approved, these experts say.

More on the U.S. Supreme Court

- Uncomfortable Revelations: Democratic lawmakers reiterated calls to tighten ethics rules for the Supreme Court after ProPublica reported that Justice Clarence Thomas had accepted luxury gifts and travel from a major conservative donor without disclosing them.

- Trans Athletes: The Supreme Court issued a temporary order allowing a transgender girl to compete on the girls’ track team at a West Virginia middle school.

- A Constitutional Test: Two criminal defendants have asked the Supreme Court to decide whether testimony given remotely against them during the pandemic violated the Sixth Amendment’s confrontation clause.

This year, two federal lawsuits have been filed against state bans or restrictions on medication abortion, claiming that the F.D.A.’s authority cannot be second-guessed by states. The lawsuits — one filed by a mifepristone manufacturer, GenBioPro, challenging West Virginia’s abortion ban and the other filed by an obstetrician-gynecologist challenging the additional restrictions North Carolina applies to medication abortion — assert that the actions of these two states are unconstitutional.

The cases contend that state abortion bans and restrictions violate the Constitution’s commerce clause, which prohibits states from impairing interstate commerce, and the supremacy clause, which says that federal laws — in this case, Congress’s decision to authorize the F.D.A. to regulate drugs like mifepristone — have priority over conflicting state laws.

“Under the U.S. Constitution, federal law preempts state law when the two clash,” Patricia Zettler, a law professor at Ohio State, and Ameet Sarpatwari, a lawyer and assistant professor of medicine at Harvard Medical School, wrote in an article in The New England Journal of Medicine last year.

This theory has rarely been tested in court. One of the few relevant cases involved an effort by Massachusetts about a decade ago to ban a new opioid, Zohydro ER, because state officials worried that the drug could be abused, leading to addiction or overdose. A federal judge sided with the drug company, Zogenix. If the state “were able to countermand the F.D.A.’s determinations and substitute its own requirements, it would undermine the F.D.A.’s ability to make drugs available to promote and protect the public health,” the judge wrote. Subsequent efforts by Massachusetts to restrict Zohydro were also rejected by the courts.

A decision like the one in Texas “represents judicial interference in really the core function of the F.D.A. and handcuffs F.D.A. in making future safety and effectiveness decisions,” Dr. Sarpatwari said.

Upending the F.D.A.’s authority could be disruptive to the U.S. pharmaceutical industry, which banks on a yearslong window of drug sales as it funds the risky and expensive process of drug discovery, said I. Glenn Cohen, a Harvard Law School professor and bioethics expert.

“If your approval can be withdrawn at a moment’s notice by a single judge,” said Professor Cohen, who was also an author of a brief supporting the F.D.A., “it’s really kind of a scary thing.”

The F.D.A. often reviews new data on drugs after they have been approved. That is especially the case with mifepristone, which is one of only 60 drugs that is regulated under a framework of extra restrictions and which has repeatedly been re-evaluated.

The agency has, on rare occasions, pressured drugmakers to pull medications from the market when there was new evidence of greater safety and health risks to patients. For example, in 2020, the agency asked Eisai to revoke its weight-loss drug Belviq after data found an increased risk of cancer.

In 2004, Merck volunteered to take the blockbuster pain medication Vioxx off the market when it discovered that the drug doubled patients’ risk of heart attacks and strokes.

Professor Charo said a decision to invalidate an F.D.A. drug approval could have ripple effects for other federal agencies with technical expertise, including those that oversee regulations related to the environmental, energy and digital communications.

“Imagine what you could do when you’ve got commercial interests that are upset about a whole slew of” issues, Professor Charo said, adding, “There’s just no end to this really.”