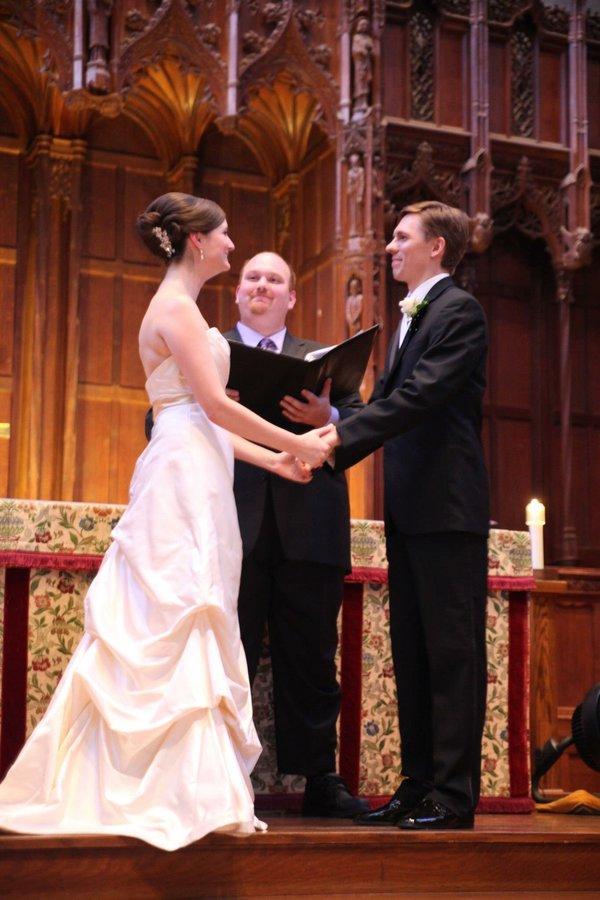

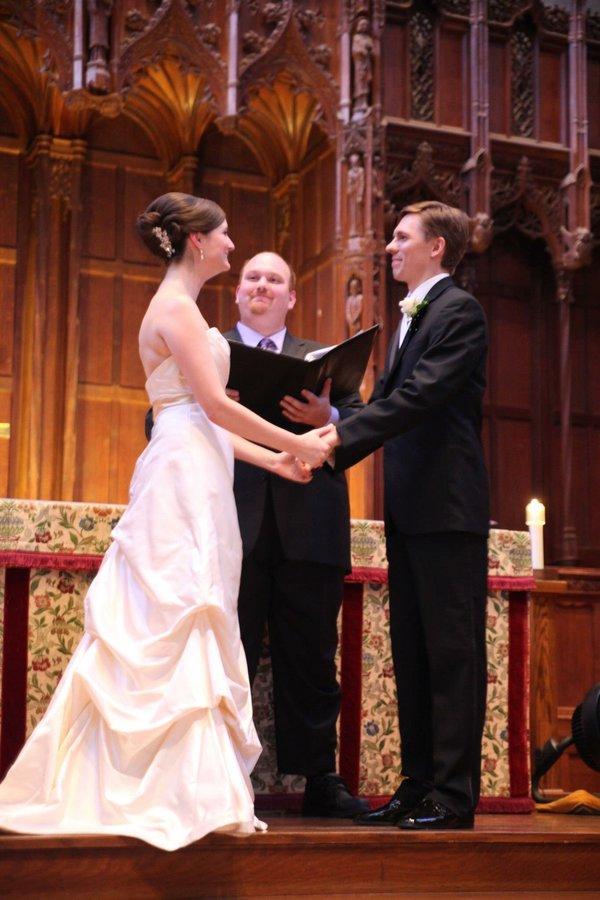

Jonathan Elliott officiated at several weddings as a Universal Life minister, but stopped marrying couples after he started working for the Episcopal Diocese of New Jersey.CreditElizabeth Massa

Jonathan Elliott had zero experience and credentials obtained in three minutes online when he performed his first wedding in 2011 in Princeton, N.J. But he didn’t make rookie mistakes, like asking guests to be seated halfway through the ceremony, or as was the case with one bumbling officiant, fumbling the pass off of the rings and dropping them into a lake.

Instead, he was so magnetic a speaker and so conscientious a master of ceremonies for Sarah Gosnell and Jed Peterson, the couple he married, that several other friends asked him to lead their wedding ceremonies. By November 2016, he had put his online certification to use 20 times. Then he started a job as communications director for the Episcopal Diocese of New Jersey, and his days of marrying friends were over.

“I was so impressed by the depth and intensity of thought put into every ceremony by clergy that I decided to stop marrying people out of respect, even though I loved doing it,” said Mr. Elliott, who is from Hamilton, N.J. The training his Episcopalian colleagues brought to weddings, he said, made the power given him by the Universal Life Church, the most popular site for becoming a minister online, feel misplaced. “It seemed like an encouraged abuse of power,” he said.

Dusty Hoesly, a doctoral candidate in religious studies at the University of California, Santa Barbara, wrote his dissertation on the Universal Life Church. He is also a ULC minister.CreditCourtesy of Jon Hall

Mr. Elliott’s opinions are not widely shared. In fact, according to the wedding industry data tracking company the Wedding Report, 25.7 percent of couples were married by a friend or family member in 2017, up from 16.4 percent in 2010. And according to Dusty Hoesly, a doctoral candidate in religious studies at the University of California, Santa Barbara who wrote his dissertation on the Universal Life Church’s role in contemporary weddings, the trend is likely to continue apace. Why? Because “the ULC and its ministers are at the forefront of religious freedom, marriage equality and nuptial creativity,” Mr. Hoesly said. As people under 30, the demographic most apt to marry, become increasingly nonreligious, their weddings will follow suit, he said, adding that there are now 23 million ULC ministers.

That’s not great news for religious and other professional officiants, who would like more online ministers to adopt Mr. Elliott’s perspective. Below, a cross-section of their criticisms, plus a counterargument from celebrity ULC minister Bobby Berk who, at last count, had received more than 1,000 Twitter requests to perform wedding ceremonies for strangers.

The Rev. Laura C. Cannon at a same-sex marriage ceremony.CreditDenis Largeron Photography

The Spokeswoman

Rev. Laura C. Cannon, Ellicott City, Md.

Ms. Cannon, the senior minister at SOUL Community Church in Columbia, Md., co-founded the International Association of Professional Wedding Officiants in 2015 to unite her colleagues and educate the public about the risks of enlisting amateur officiants. A handful of states do not recognize marriages performed by Universal Life ministers, including several counties in New York, and some divorces have been complicated by questions over their validity, said the Rev. Cannon, the senior minister at Soul Community Church, a Universalist congregation in Columbia, Md. More frequently, novice officiants bungle the paperwork needed to solemnize a union. “You want your wedding to be legal,” she said. “Otherwise, it’s just an expensive party. Just because your family member can use a camera doesn’t mean you’d hire him to be your photographer. People in our organization understand marriage laws.”

Jessie Blum of Montclair, N.J., became an officiant after enrolling in an online course at the Celebrant Foundation and Institute.CreditLily Szabo

The Certified Celebrant

Jessie Blum, Montclair, N.J.

A celebrant performs alternative ceremonies, including same-sex and nonreligious weddings. Ms. Blum became one in 2009, eight months after enrolling in an online course at the Celebrant Foundation and Institute. “The reason I chose the institute instead of getting ordained online was I wanted strong knowledge of how to perform ceremonies,” Ms. Blum said. “I’ve had people come to me and say, ‘I’d really like you to officiate, but if you can’t do it I’m just going to get my florist to do it.’ You have to spend a lot of time getting to know a couple if you want to make it special. People don’t understand how much work goes into it.”

Lisa Antonecchia, a justice of the peace in Connecticut, says couples should work with professional officiants. “We make sure everything is buttoned up and done,” she said.CreditVicki + Erik Photography

The Justice of the Peace

Lisa Antonecchia, Hamden, Conn.

Ms. Antonecchia, the owner of the wedding planning service Creative Concepts by Lisa, became a Connecticut justice of the peace in case of emergencies — the kind she said she is seeing more of as couples increasingly rely on one-off officiants. In 2013, a wedding she planned on the Connecticut shoreline was nearly derailed by a newly minted officiant stuck in traffic. “He finally made it, but from that point on, I knew I wanted to be able to offer the service myself,” she said. Which is why she recommends professionals. “We make sure everything is buttoned up and done. Your Uncle George may be a great guy. But what if his flight gets delayed and he misses the wedding?”

Cantor Debbi Ballard upholds religious standards for ceremonies that include Jewish traditions.CreditRoger Edelman Photograph

The Cantor

Cantor Debbi Ballard, Fort Lauderdale, Fla.

Ms. Ballard specializes in weddings that have at least one Jewish partner. “Couples who use friends and family members to marry them often want to dip into the religious aspect very lightly with one or two rituals, like the breaking of the glass,” she said. “But that’s not what makes a Jewish wedding a Jewish wedding.” In addition to upholding religious standards, “I’m going to see that the day is seamless and easy for the bride and groom. If your sister is marrying you, she’s so nervous about her performance she’s only thinking about herself. It’s not going to be a well-facilitated and organized experience.”

The comedian Harris Bloom became a ULC minister in 2013 so he could officiate at a wedding for a fan of his standup routine.CreditDave Robbins Photography

The Comedian

Harris Bloom, Manhattan

Mr. Bloom became a ULC minister in 2013 to orchestrate a wedding for a fan of his standup comedy routine. Now marrying strangers, which he does about 150 times a year, is his primary source of income. Friends and families generally don’t charge for their services, but he said his typical fee of $600 — steeper than the $214 the Wedding Report tallied as the average officiant expenditure in 2017 — is money well spent. “I think most people think of the ceremony as something they have to get through to get to the party,” he said. “I thought that way myself before I started doing weddings.” Now he knows better. “If a kid starts losing it during the procession, I know how to deal with it. If the best man forgets the ring, I’ll lighten the mood with a joke. I can make the ceremony the highlight of your wedding. That’s probably what you want on the most important day of your life.”

Bobby Berk of “Queer Eye,” clad in a bright orange suit, has gotten many request to officiate at weddings since becoming a ULC minister.CreditKelly Bach Photography

The Celebrity and ULC Proponent

Bobby Berk, Los Angeles

Mr. Berk, the interior design guru from Netflix’s “Queer Eye,” married three couples in June at the New York City Pride Parade. He was ordained a ULC minister for the event and has since been flooded with pleas, via social media, to do more. “I’ve already got a couple thousand requests just on Twitter,” he said. If he could marry every couple who asked, he would. “I never thought I’d be crying on a parade float, but there I was. It was such an honor.” Mr. Berk knows firsthand that the chances of uncrossed t’s and undotted i’s increase when a professional is not presiding. A friend who officiated his own wedding, in 2012, forgot to file documents to legalize the union. “He never sent in the correct paperwork,” he said. “We found out at the end of the year when we were like, ‘Why did we never receive our marriage certificate?’” Mr. Berk and his husband were remarried at the New York City Courthouse at the end of the year so they could file their taxes jointly. But he didn’t mind. “You used to have to get married in a courthouse or a church. Now it’s more personal. It’s way more special,” he said.