Puberty hit C early — in the fourth grade — and hard: acne, breasts, attention, humiliation. C found refuge in the internet.

Every night, often well past midnight, C lay in bed with an iPod Touch they received from their grandparents as a 10th birthday gift. (C, who is being identified by their first initial for privacy reasons, is gender nonbinary and takes the pronoun “they.”) On the new device, C made friends on social media and uploaded selfies. Viewers posted compliments on a photo of C standing in an orchard, holding an apple and “looking like a full adult,” C said.

Less welcome were the comments from men who sent pictures of their genitals and asked C for nude images and for sex. “I had no idea what was happening,” C, who is now 22 and lives in Salt Lake City, said. “What do you do when someone’s just, like, sending you gross stuff in your inbox? Nothing. Just ignore it.”

That plan did not work out. The internet seeped into C’s psyche; severely depressed, they found kinship online with other struggling adolescents and learned ways to self-harm.

“I don’t want to blame the internet, but I do want to blame the internet,” C said. “I feel like if I was born in 2000 B.C. in the Alps, I’d still be depressive, but I think it’s wildly exacerbated by the climate we live in.”

A yearlong series of articles by The Times has explored how the major risks to adolescents have shifted sharply in recent decades, from drinking, drugs and teen pregnancy to anxiety, depression, self-harm and suicide. The decline in adolescent mental health was underway before the pandemic; now it is a full-blown crisis, affecting young people across economic, racial and gender lines.

The trend has coincided with teenagers spending a growing amount of time online, and social media is commonly blamed for the crisis. In a widely covered study in 2021 first reported by The Wall Street Journal, Meta (formerly Facebook) found that 40 percent of girls on Instagram, which Meta owns, reported feeling unattractive because of social comparisons they experienced using the platform.

The reality is more complex. What science increasingly shows is that virtual interactions can have a powerful impact, positive or negative, depending on a person’s underlying emotional state.

“The internet is a volume knob, an amplifier and accelerant,” Byron Reeves, a professor of communication at Stanford University, said.

But there is a lack of reliable research into how technology affects the brain, and a shortage of funding to help ailing teens cope. From 2005 to 2015, funding from the National Institute of Mental Health to study innovative ways to understand and help adolescents with mental health issues fell 42 percent.

“The federal funding, or lack thereof, has contributed enormously to the place we’re at,” said Kimberly Hoagwood, a child and adolescent psychiatrist at NYU Langone Health and former associate director for child and adolescent mental health research at the N.I.M.H. “We’ve sort of put our blinders on.”

Dr. Joshua Gordon, the current director of the institute, said, “We don’t have tremendous insights into why it’s happening.”

But there are powerful clues, experts said. They widely posit that heavy technology use is interacting with a key biological factor: the onset of puberty, which is happening earlier than ever. Puberty makes adolescents highly sensitive to social information — whether they are liked, whether they have friends, where they fit in. Adults face the same onslaught, but pubescent teens encounter it before other parts of the brain have fully developed to handle it.

“On a content level, and on a process level, it makes your head explode,” said Stephen Hinshaw, a psychologist at the University of California, Berkeley. “You want to make it stop — cutting yourself, burning, mutilation and suicide attempts.”

How to Help Teens Struggling With Mental Health

How to Help Teens Struggling With Mental Health

Recognize the signs. Anxiety and depression are different issues but they do share some indicators. Look for changes in a youth’s behavior, such as disinterest in eating or altered sleep patterns. A teen in distress may express excessive worry, hopelessness or profound sadness.

The ability of youth to cope has been further eroded by declines in sleep, exercise and in-person connection, which all have fallen as screen time has gone up. Young people, despite vast virtual connections, or maybe because of them, report being lonelier than any other generation. And many studies have found that adolescents who spend more time online are less happy.

Still, many questions remain. This is partly because the internet experience is so vast and varied, health experts say, which makes it hard to generalize about how screen time — and how much of it — leads to anxiety and depression.

“That doesn’t mean there’s not a relationship,” Dr. Reeves said. “There are so many effects that are totally idiosyncratic to individual kids.” He added, “Each of their experiences are so radically different.”

An outside connection

C grew up in an upper-middle-class family and displayed a gift for music from an early age. An uncle remembered C at 8 playing a flawless “Für Elise” on piano, with a bubbly Shirley Temple vibe. “An incredible talent, we were thinking Juilliard,” he said.

Mental health challenges ran in C’s family. In third grade, C began obsessively digging a pencil into one leg. Shortly after, puberty hit — “crazy early,” C recalled. “I was still in elementary school and suddenly my brain is, you know, working like 20 times faster on the dark stuff.”

At 10, C joined Mini Nation, a virtual community where they hoped to find friendship but instead faced harassment from men. C didn’t tell their parents, fearing they would take away the iPod. “It was my connection to the outside world,” C said.

The cutting intensified. “Self-harm was like a smoke break,” C said. “I would do it, watch a little YouTube, take a break, knife, come back.”

After classmates told a school counselor about the wounds on C’s arms, C spent a week in a psychiatric hospital, was prescribed Zoloft, and was sent home.

C’s family moved to Utah, hoping for a fresh start. But the challenges plaguing C could be found everywhere. From 2007 to 2016, emergency room visits for people aged 5 to 17 rose 117 percent for anxiety disorders, 44 percent for mood disorders and 40 percent for attention disorders, while overall pediatric visits were stable. The same study, published in Pediatrics in 2020, found that visits for deliberate self-harm rose 329 percent. But visits for alcohol-related problems dropped 39 percent, reflecting the change in the kind of public health risks posed to teenagers.

Dr. Karen Manotas, a child and adolescent psychiatrist at the University of Utah, said that social media sometimes seemed to play a role in the adolescent mental health cases she handled. Last September, Dr. Manotas treated a 15-year-old boy in the hospital who had attempted suicide after learning of his girlfriend’s infidelity. When he decided to forgive her, the boy’s friends turned on him with “an online group text chat about him being a sucker.”

Around that time, Dr. Manotas was seeing a 15-year-old girl predisposed to anxiety and depression who had developed a tic disorder, yelling out noises in public and turning her neck obsessively. The girl, Dr. Manotas learned, had identified closely with “Tik Tok influencers” whose tic disorders the girl seemed to adopt to perfection. “It was the exact neck tic this girl presented with,” Dr. Manotas said. “I was floored.”

Dr. Manotas noted that the girl’s tics were expressed in some circumstances but not others, and she ultimately concluded that the girl had been influenced by social contagion. (The girl subsequently sought care in an inpatient setting, and Dr. Manotas did not know how her condition resolved.)

“It’s like this sense of belonging and community that doesn’t really exist but they believe that it does,” Dr. Manotas said. “A lot of kids and teens are resorting to these online communities as a way to find belonging and who they are.”

‘A double whammy’

Since 1900, the average age of the onset of puberty for girls has fallen to 12 from 14, a shift that health experts attribute in part to improvements in nutrition. (Puberty occurs about a year later for boys than for girls, and its onset has fallen, too.) In puberty, the brain is flooded with hormones and other neurochemicals that, among other things, render a young adolescent more sensitive to changes in social cues, according to brain-imaging research by Andrew Meltzoff, co-director of the University of Washington Institute for Learning and Brain Sciences.

But the regions of the brain responsible for self-regulation do not develop any faster or earlier than before. Psychosocial maturity — a person’s ability to exercise self-restraint in emotional situations — does not fully mature until the 20s, according to a 2019 paper published by the American Psychological Association that drew on research involving 5,000 teens from 11 countries.

Now, the combination of early puberty and information overload presents “a double whammy” that can lead to “anxiety and depression when people feel a lack of control,” Dr. Meltzoff said.

Researchers have been framing the issue around a particular set of questions: Is social media to blame for the rise in adolescent emotional distress? Is this a problem associated with consuming one type of information?

The results of numerous studies are conflicting, with some finding that heavy use of social media is associated with depressive symptoms and others finding little or no connection.

A 2018 study of lesbian, gay and bisexual teens found that social media was a double-edged sword, opening up new support networks but also exposing adolescents to animosity. “There are literally thousands of hate messages in an instant,” said Gary Harper, a professor of behavioral health at the University of Michigan.

At the same time, he said, social media also provides validation and community: “It’s good to have a variety of ways we can be, that affirms diverse identities.” He added, “But your brain needs to develop enough to sort through all that information.”

A 2019 study in the Netherlands reached a similarly equivocal conclusion. Over three weeks, the researchers asked 353 adolescents to report six times a day how often they had browsed Instagram and Snapchat in the past hour and to note how they had felt in that time and at the moment of reporting. Twenty percent of teens who used their phones to access social media said they felt worse — but 17 percent reported that their mood had improved.

The most reliable conclusion, researchers say, is that some teens are more vulnerable than others.

“Children can react very differently,” said Patti Valkenburg, founder and director of Center for Research on Children, Adolescents and the Media at the University of Amsterdam, and co-author of the Dutch study. For instance, when they encounter people online who appear successful, “some can be envious and others can be inspired,” Dr. Valkenburg said.

Absent clear answers, some researchers have begun to reframe the core question: not how much screen time is too much, but which activities known to be healthful might screen time be displacing?

These activities include sleep, time spent with family and friends, and time spent outdoors and being physical. Sleep looms particularly large. In 2020, a multiyear study involving nearly 4,800 teens found a close relationship between poor sleep and mental health issues. Participants with a diagnosis of depression got less than seven and a half hours of sleep per night, compared with the eight to 10 hours recommended by the National Sleep Foundation for people 14 to 17.

Poor sleep is a “fork in the road, where a teen’s mental health can deteriorate if not treated,” Michael Gradisar, a clinical child psychologist at Flinders University in Australia, said in a news release accompanying the study.

A shortage of sleep makes it even harder for the brain to regulate and process emotional challenges, multiple studies have found. Many experts recommend that parents enforce a no-device policy for an hour before bedtime and that they redirect young people to in-person, outdoor activities during the day.

Dr. Kara Bagot, a child and adolescent psychiatrist at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, noted that ample research showed the benefits of rest, exercise, imaginative and in-person play, whereas the impact of heavy screen time was uncertain. “We don’t know what can happen, and childhood is such an important developmental period for brain development, for social development,” Dr. Bagot said.

That uncertainty, she added, results in part from the “huge mismatch” between the billions of dollars spent by tech companies to attract users and the modest funding available to researchers like her to study the impact. “It’s only going to get worse,” she said. “The tech keeps getting better and more advanced over time, and more engaging.”

Major research efforts, such as the federally funded Adolescent Brain Cognitive Development study, are still in their early stages. The study follows 12,000 youth in the United States and includes questionnaires, behavioral studies and expansive neuroimaging to understand brain development and function. The study began in 2015 with an emphasis on substance abuse but has grown to trying to understand the impact of screen time.

Dr. Gordon, director of the National Institute of Mental Health, said the government wanted more research but was not receiving enough funding applications from scientists.

“There’s not enough psychiatric care, not enough social workers to treat kids,” he said. “Even worse than that is the shortage of child mental health researchers. It’s a real problem.”

Two decades ago, public service campaigns encouraged adolescents to “just say no” to drugs, to practice safe sex and to find a designated driver. Today’s health experts are having a harder time offering adolescents like C reliable, hard-and-fast guidelines for handling screen time and social media, said Dr. Hoagwood, the former associate director at the N.I.M.H.: “We can’t just tell her she shouldn’t have spent so much time on social media and then she’d be OK.”

A stage of their own

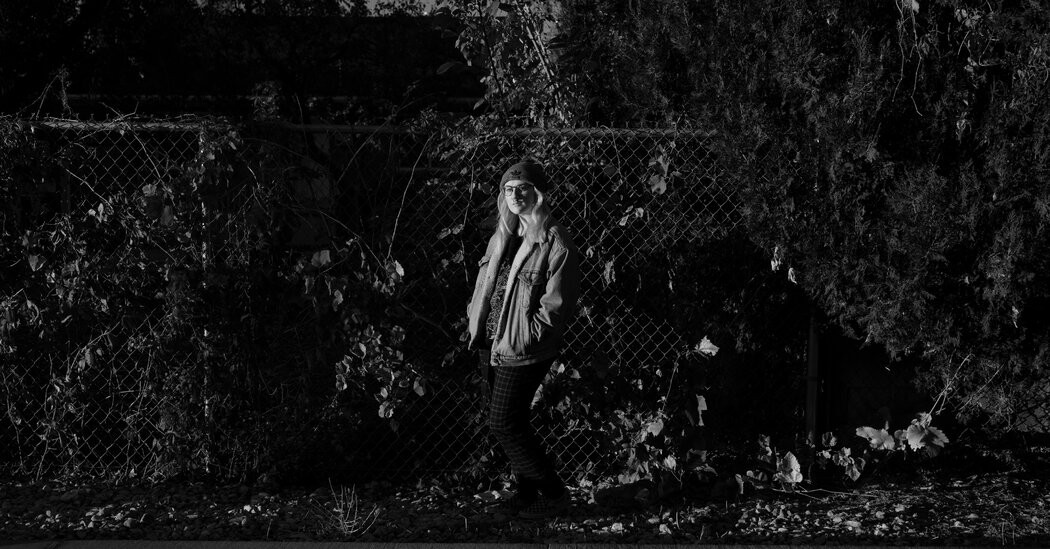

In July, C stood at the edge of a music stage in Denver, rings in each nostril and dark makeup expertly drawn to resemble a cat’s eyes.

“I love that face!” a friend wrote on C’s Facebook page. “Best eyes ev.” C hearted the comment.

After years of pain and self-discovery, C’s relationship to the internet underwent a dramatic shift. There was an eating disorder, more cutting, the pressure of school, the agonizing pain of depression.

At 15, C was hospitalized for a week, and at 18 for longer, after C took “a bunch of pills, everything I could find.”

“How would you believe it’s going to get better when you’re growing into your adult brain but still treated like a child?” C said. “And you have depression. It’s like, Wow, this is it, this is what’s waiting for me — cool, I’m out, I want to die.”

During their second hospitalization, C met with a psychiatrist and discussed the online abuse from years earlier. “It was the first time I admitted out loud that all the time I spent online since I was 10 was maybe counterproductive to my health,” C said.

During the pandemic, C adopted the pronoun “they.” The change reflected their understanding that they have “power over how people perceive me and how I perceive myself,” C said. “Instead of accepting the role that was put on me, I’ve made my own.”

This spring C completed an undergraduate degree in speech and hearing science. They are also a singer, songwriter and keyboardist with a rock band, Lane & the Chain, which has a growing following. In Denver, C played with a band called Sunfish.

“Now that I’m alive, I want to be alive and pursue music,” C said. That includes being comfortable appearing in online music videos and other social media: “I’m more complex than just being a little girl on the internet who’s, you know, just for looking at.”

C added: “In my adult nonbinary body, I don’t mind people looking at me, because I feel like I’m in control now.”

Kassie Bracken contributed reporting.