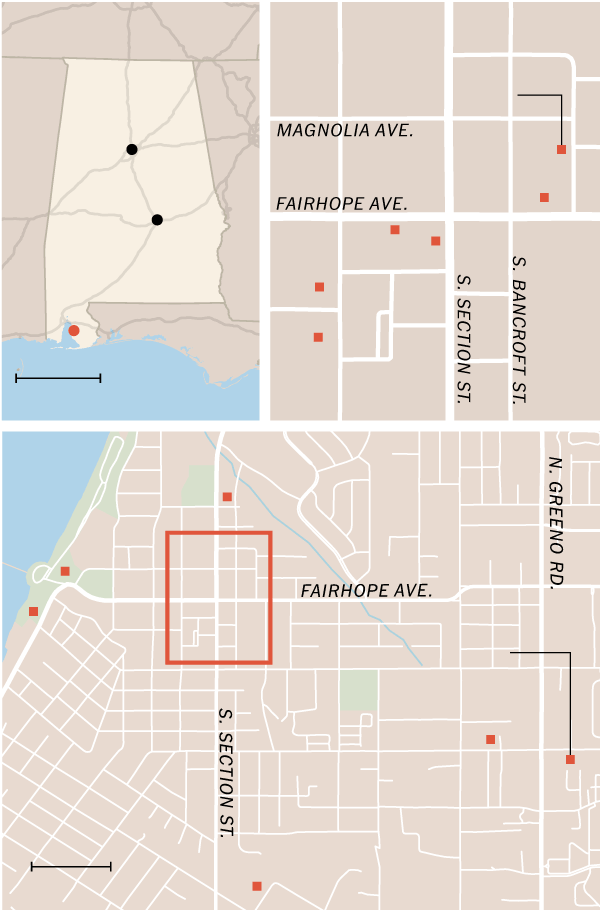

A group of populist reformers from up north arrived in Alabama in November 1894 with a radical plan. Their mission: to establish an experimental utopian community inspired by the economist Henry George, whose wildly popular book, “Progress and Poverty,” influenced readers around the world in search of more equitable societies. In this case, their chosen setting was a swath of pine- and pasture-covered land perched high on a bluff overlooking Mobile Bay. There, wrote one of the founders, Ernest B. Gaston, these pioneers would build “a city set upon a hill, shedding its beneficent light to all the world.” Somewhat more modestly, they christened their settlement Fairhope, asserting that their dream community would have “a fair hope” of succeeding.

Henry George’s acolytes put their faith in his concept of a “single tax” colony where the community owned the land and homeowners paid an annual tax that funded the creation of parks and public amenities. The founders set aside nearly a mile of beachfront as public parkland, writes a local historian, Cathy Donelson, in her book, “Fairhope.” They quickly drew more settlers — and soon vacationers, too. Early tourists arrived by steamboat, enticed with attractions like the giant water slide that deposited frolickers directly into the bay, while the annual Shakespeare festival offered free outdoor performances that used the scenic natural setting as a stage.

Fairhope’s blend of natural beauty and eccentric ambition continued to attract artists, writers and intellectuals. The noted progressive educator, Marietta Johnson, opened her School of Organic Education in town. Clarence Darrow, the original super-lawyer, was a fan of the single-tax philosophy and wintered in Fairhope in the 1920s and ’30s. Upton Sinclair wrote his novel “Love’s Pilgrimage” in a tent on the bluff.

A century later, Fairhope is still a draw for writers seeking a peaceful retreat, for art lovers — most notably during the annual Fairhope Arts & Crafts Festival in March — and for many other vacationers, no shortage of whom fall for this unheralded setting and decide to stay.

“It’s just a magical little place,” said the author Fannie Flagg. “There are people that have come there from all over the world. Once they see it, there’s a charm about it that they just love.” Ms. Flagg was born in Birmingham and first visited Fairhope as a child. She was lured back years later. “When I started writing, I was living in New York and wanted a place to get away, so I thought, ‘Why don’t I go down to Fairhope?’” She wrote her first book in Fairhope, then returned again to pen the Oscar-nominated screenplay for “Fried Green Tomatoes.” She kept a home in Fairhope for many years, and still returns frequently.

The Fairhope Center for the Writing Arts sponsors a writers-in-residence program, providing monthlong stays at the center.CreditRobert Rausch for The New York Times

“I don’t know what it is, but there’s an amazing amount of artistic talent that is all gathered here in this one place,” said the writer Sonny Brewer, who has lived in Fairhope since 1978. Mr. Brewer, who formerly ran a bookstore in town, founded the Fairhope Center for the Writing Arts, which invites writers-in-residence for monthlong stays in a 1920s cottage tucked behind the city’s public library. Fellow scribes, Mr. Brewer said, have joked about erecting a billboard welcoming visitors to “Fairhope, Alabama, the home of more writers than readers.”

A serene pace of life

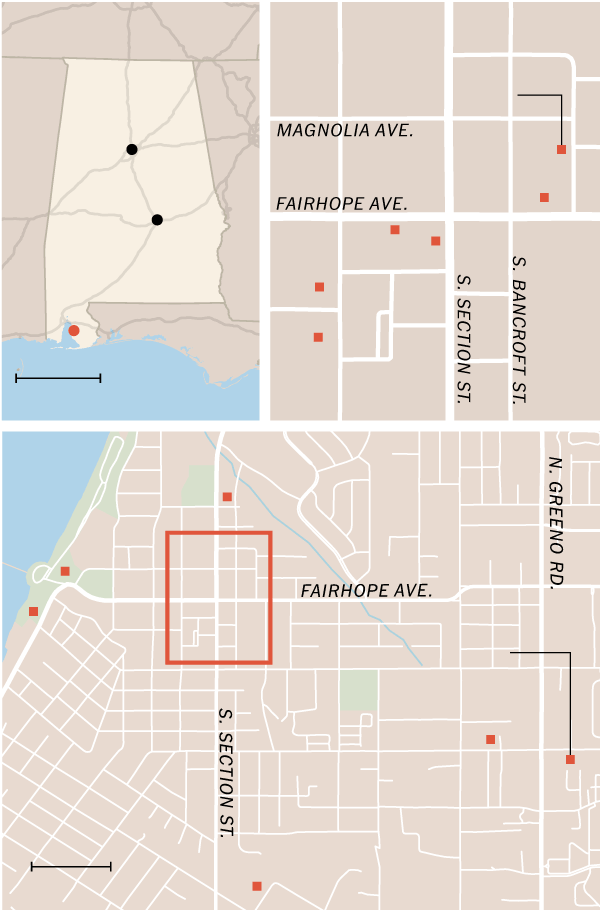

Today, Fairhope is still anchored by its public beachfront, with scenic views available from the Municipal Pier that stretches 1,448 feet out over the bucolic bay, and from the tree-lined Henry George Park up on the bluff. A short stroll up the hill, past shady streets where rocking chairs sway on porches, is the very walkable downtown. Sidewalks are filled with more than a dozen different public art pieces and copious flowers in all seasons, from beds of petunias in summer to snapdragons in the dead of winter. New and historic buildings are home to antique stores such as Crown & Colony, indie boutiques, and galleries like Eastern Shore Art Center, which runs a first Friday art walk.

Charming cafes and restaurants abound, a mix of longtime local favorites like Julwin’s, a greasy spoon that dates to 1945, and hipper newcomers like Refuge Coffee, where a young woman in a hijab recently sipped espresso next to a couple with copious face piercings, and a retiree from Seattle warned that “they’re a little snobby about their coffee here.” Most Fairhope venues fall somewhere in between, like Locals, a small, no-frills space where grass-fed-lamb burgers and elderberry kombucha are on the menu.

From March 15 to 17 this year, a large part of downtown will be taken over by the 67th annual Fairhope Arts and Crafts Festival, which brings in more than 300,000 visitors. Streets are closed to traffic and given over to wares from nearly 200 different artists, along with performances from the likes of jazz bands and dance crews. Later in spring there are sunset concerts near the bay by the Baldwin Pops, while fall brings the Fairhope Film Festival, including outdoor screenings in an amphitheater downtown.

The place where Fairhope’s founding spirit is most alive is perhaps Page and Palette, an independent bookstore that has stood near the center of town for over 50 years. The bar and event space hosts eclectic audiences for readings and performances several evenings each week, and regulars fill the on-site coffee shop. On Tuesdays and Thursdays for the past decade, two longtime locals have operated “Sonya and Nancye’s Friendly Advice booth” inside the coffee shop, sitting behind a wooden booth inspired by Lucy from the “Peanuts” comic strip and doling out sage advice for a nickel per customer.

“The two of them were just great, loyal customers,” said Page and Palette’s owner, Karin Wilson. “When the bottom fell out in 2008, we really thought we were going to have to close. They were very concerned about our store; they wanted to meet with me and ask how they could help. We were meeting in the coffee shop and someone said something along the lines of, ‘What are ya’ll doing here?’ One of them said, ‘Oh, we’re solving the world’s problems.’ I jokingly said they should do an advice booth, and the idea stuck. They’ve been here every Tuesday and Thursday since,” offering thoughts and comfort to anyone in need of a friendly ear. “They’re two women that everyone feels comfortable talking to. It’s something very special that they created.”

A plan for smart development

Ms. Wilson’s grandmother opened Page and Palette as an art supply and book store in 1968; her father eventually spun off a frame shop and gallery next door. Ms. Wilson bought the bookstore in 1997, adding the coffee shop and bar/event space, while her twin sister, Kelley Lyons, purchased the frame shop, now Lyons Share Custom Framing and Gallery.

In a twist, the independent bookseller is now also the city’s mayor — Karin Wilson jumped into politics in 2016 with a successful campaign centered around a platform of smart development. Fairhope is now one of Alabama’s fastest growing cities, with a 27 percent growth in population from 2010 to 2017.

“There’s this charm that we don’t want to lose,” Mayor Wilson said. “Owning the store, we meet so many people who say, ‘We’ve always wanted to live in a community like this.’ People choose to be here for a very specific reason and they’re very motivated about keeping it that way.”

Certainly, there’s much about modern Fairhope that seems a far cry from its socialist-leaning heyday. The Fairhope Single Tax Corporation maintains a charming old-world office on Fairhope Avenue, but today it owns only about 20 percent of the land in Fairhope. Those who live on that 20 percent technically lease the land and pay a single tax to the FSTC that includes their property taxes and a small fee. The other 80 percent of homeowners own the land beneath their homes. All are free to buy and sell as they please. Historic homes along the waterfront can get multimillion-dollar prices.

For visitors, there are a host of rental homes scattered around downtown, plus elegant inns and B&Bs like Emma’s Bay House near the water. Just south of Fairhope is the Grand Hotel, a sweeping 172-year-old property set on a 550-acre expanse that includes two golf courses and a spa. The city’s rapid development means there are now enticing new spots further afield, like the Fairhope Brewing Company, which opened in 2013 in a former tabletop manufacturing facility about a mile from the main stretch of downtown. A huge mural of an oak tree sprouting hops instead of leaves covers the outside of the adjacent bottling building (the artist, Sarah Rutledge Fischer, is the wife of one of the brewers).

The brewery also makes a coffee stout with beans sourced down the road at Fairhope Roasting Company, which shares a garage-door-fronted space with Warehouse Bakery & Donuts. The latter serves up old-style chocolate glazed doughnuts, and more new-school breakfast biscuits stuffed with fried eggs, small-batch bacon and spicy mayo. One door down at District Hall, there’s rock ‘n’ roll bingo with whiskey-infused burgers.

It’s still the serene pace of life that lures most people to Fairhope.

“When I was working on ‘Fried Green Tomatoes’ here,” Fannie Flagg recalled, “writing a screenplay is so very difficult and some days I thought I would just pull my hair out. Every afternoon, I would walk across the street from my house and out onto the pier. I would sit there and watch the sun go down. The church was right behind me. The bells would ring and it would just be so peaceful right there in that spot. It kept me sane.”

Follow NY Times Travel on Twitter, Instagram and Facebook. Get weekly updates from our Travel Dispatch newsletter, with tips on traveling smarter, destination coverage and photos from all over the world.