“Kagami,” the new “mixed reality” concert of Ryuichi Sakamoto’s music by the production company Tin Drum is meant to be a profound experience, a groundbreaking achievement in virtual reality that expands the visual limits of recorded performance. In practice, it feels like a wake in a laser tag arena. In some ways that’s unavoidable; Sakamoto, one of Japan’s most internationally recognized artists, died in March, so any presentation of his music so soon is hard pressed to avoid a funereal pallor. This one doesn’t escape that fate.

For the occasion, the Shed’s Griffin Theater greets guests with an antechamber cast in sepulchral light and hung with wall size images from Sakamoto’s life. Scenes from the 2017 documentary “Ryuichi Sakamoto: Coda” play on mute on the far wall — Sakamoto collecting rainwater in a bucket; sampling the sound of an ice floe in the Arctic Circle — which, out of context, seem more oblique than they really are.

The actual performance takes place beyond a curtain in an empty black box theater, which, materially speaking, stays that way. Besides the genial attendants who fit you with the required, vaguely steampunk headsets, and the presumably very expensive virtual projection equipment, there is nothing — no live performers, no props, no screens. You sit in the round, staring at a glowing, virtual red cube in the center of the room, which suggests a séance administered by an AV club.

The Sakamoto that blinks to life in a taped-off zone appears beamed in from what is usually called the uncanny valley but is perhaps more accurately translated as “the valley of eeriness.” This version of Sakamoto winces and screws up his face just as the real one did. Light glints off the silver of his elegant center-part. You can see the hammers of his virtual grand piano twitch as he moves through a brisk 50-minute tour of his solo oeuvre, from his late-80s hit film scores and spare ’90s piano arrangements to his later textural ambient requiems. Sakamoto, though close, doesn’t look entirely human — his skin too smooth, an unnatural light seeming to emanate from his body. He is both there and not there. It is, in other words, like looking at a ghost.

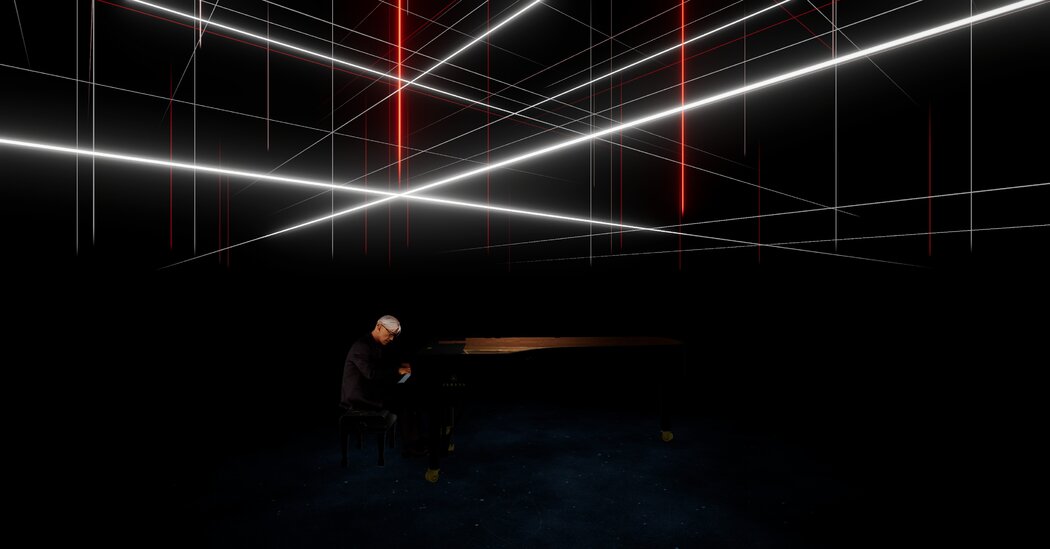

Tin Drum did something similar with “The Life,” in 2019, loosing a three-dimensional Marina Abramovic avatar within a roped-off pen at the Serpentine Galleries in London. Here they improve on that spectacle slightly. Where “The Life” was a relatively simplistic rendering of Abramovic’s milling around, “Kagami” incorporates a series of flashy visual effects that accompany Sakamoto’s playing: curling smoke that draws in at his ankles; a grid of fluorescent beams overhead, à la “Tron”; a carousel of anodyne postcard views. Most of these are pretty to look at but are head-scratching, distracting, or both, like the portal to a winter forest that opens during “Energy Flow,” projecting a shaft of light onto Sakamoto’s back, or the floor that gives way to a twinkling cosmos during “Merry Christmas, Mr. Lawrence,” allowing him to perch atop an Earth spinning in infinity. Their inclusion suggests a concession to those experiencing smartphone withdrawal (phone camera photography is mostly useless here, a small blessing), as if Sakamoto’s limpid playing was somehow not enough of a gift.

Like air travel, the technology underpinning “Kagami” is at once miraculous and dopily inelegant. The headset’s five pound battery pack is strung on a lanyard around your neck, and the sound of Sakamoto’s playing competes with the battery’s fan straining to keep the system from overheating, a task at which it sometimes fails. When it does, an error message fills your field of vision, which is amusing, but also dispels some of the magic.

This is not the Ganzfeld of James Turrell — the material boundaries of the room never fully fall away, a useful safety feature, as the production encourages viewers to wander around the theater, behavior that wouldn’t be tolerated at a traditional recital, and doesn’t add much here, beyond enabling the neat trick of watching a virtual golden dew drop pass through your hand. So being able to see your fellow attendees’ legs (mostly) avoids collisions.

These all may sound like necessary minor inconveniences on the road to progress. But is this progress? Being in a room with a mirage while the music is piped in is hardly more transcendent than watching a standard video recording, which, really, is what this is anyway. Tin Drum filmed Sakamoto in Tokyo over three days in December 2020, capturing both his performance and the contours of his body with 48 cameras, an immense amount of data that took five months to process. The result represents, by their accounting, the invention of around a dozen technical processes completed by designers, scientists, and engineers in as many cities — by any measure a huge undertaking.

“But the point was never the technology,” Todd Eckert, the director of “Kagami” and founder of Tin Drum, wrote to me. “We were trying to find a way to connect an artist with an audience he would never meet.” It is an inarguably noble goal, if not exactly a democratic one; this particular connection requires untold specialized equipment, and tickets go for $31 to $60 for what is effectively a film screening.

In many ways, “Kagami” is only the latest pile-up at the intersection of art and technology, a locus that’s less interchange than speed trap. While the appetite for immersive art experiences shows no sign of dampening, the realization of the concept remains less about innovation than social media bait. NFTs, more financial instrument than new art form, burned hot and fast, largely supplanted by AI imagery, which has so far mostly produced a uniformly bland style of photorealism. Art is uniquely susceptible to faddishness easily confused with human advancement.

There is something off-feeling about the likeness of Sakamoto, a lifelong anticapitalist, being projected inside the Shed, the arts-center-as-cultural-window-dressing for Hudson Yards, the largest private real estate development in New York. (“Kagami” is also premiering at Factory International, in Manchester, England). If this bothered him, though, it didn’t outweigh what he saw as the benefits. Sakamoto was also a populist, and believed, rightly, that music was for everyone (he composed a score for the Japanese chain store Muji, and originally wrote “Energy Flow,” a languid, hauntingly delicate piano ballad, for a vitamin commercial.)

Sakamoto’s willingness to attach himself to this kind of technology makes a kind of sense. Considered a godfather of electronic pop music, he loved tinkering with gizmos, and as the keyboardist in Yellow Magic Orchestra made oracular use of samplers, synthesizers, and programmable drum machines, metabolizing the futurism of late-80s Japan. The unnatural sound was an expression of his belief that all music is artificial, the forcing of nature into shape. It’s easy to imagine him seeing virtual reality as simply another instrument.

“The piano doesn’t sustain sound,” Sakamoto muses in “Coda.” “I’m fascinated by the notion of a perpetual sound, one that won’t dissipate over time. Essentially, the opposite of a piano, because the notes never fade. I suppose in literary terms, it would be like a metaphor for eternity.”

Kagami means “mirror” in Japanese, but the production offers less a reflection than a perpetual afterimage. It is both the performance and the record of it, a memory that will never fade, so long as the batteries last. It becomes, mostly despite itself, an affecting meditation on grief. This Sakamoto can’t improvise or absorb the energy of his audience. He only exists in the past. The theater is momentarily overwhelmed, but never fully, just the way the memory of a person can fill a room and just as quickly be extinguished. “Kagami” isn’t really about that; it’s about cool technology. It is an effective transcendence of death, but so is any audio or video recording, or photograph, or any piece of art. Good art, like Sakamoto’s, does that, with or without the light show.

Kagami

Through July 2, the Shed, 545 West 30th Street, Chelsea; (646) 455-3494; theshed.org.