We were around 30 miles shy of Dire Dawa, Ethiopia, when the train hit a cow, its impact signaled by an abrupt drop in speed and a sharp judder rippling through the couplings.

“What’s happening?” I asked the carriage attendant, as she hurried along the aisle.

“No problem,” she replied brightly, without breaking stride. “A technician is dealing with it.” It was only later that one of our Ethiopian neighbors told us we’d struck some errant livestock.

The passengers — my photographer Marcus Westberg and I among them — merely shrugged. We’d never kidded ourselves that this trip would be entirely without misadventure.

In the nine years since my first visit, a lot had changed in Ethiopia. The economy had boomed, with years of sustained 10 percent annual growth yielding significant jumps in life expectancy, living standards and GDP. In September, a rapprochement with Eritrea, Ethiopia’s glowering northern neighbor, brought peace to their shared border for the first time in more than 20 years.

Passengers enjoying the air-conditioned comfort of the new train between Addis Ababa and Djibouti City.CreditMarcus Westberg for The New York Times

However, for every two steps forward there has been one back. With the economic miracle stalled by drought in 2016, and anti-government riots tearing through the Oromia heartlands the same year, Ethiopia remained transitional, ill at ease with the pace of change. Last month’s horrifying crash of Ethiopian Airlines Flight 302, which killed 157 people from 35 countries, couldn’t help but recall the trauma of the late twentieth century, when Ethiopia was a place all too synonymous with tragedy.

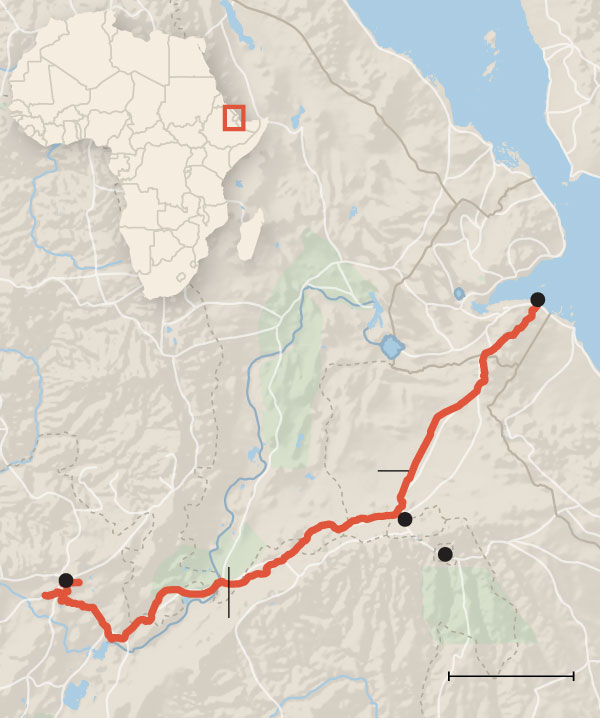

Still, the thing that had brought me back here seemed like a concrete embodiment of progress: Ethiopia now had a state-of-the-art train. In 2011, the government announced that a new electrified railway would be built between Addis Ababa and the tiny neighboring country of Djibouti, aided by Chinese loans and expertise. Five years and $3.4 billion later, the first freight train made the 470-mile journey, revolutionizing landlocked Ethiopia’s access to the Red Sea, where Djibouti’s Doraleh Port processes 95 percent of its international trade.

Area of

detail

Lake Assal

Djibouti City

Addis Ababa-

Djibouti Railway

Addis

Ababa

Awash National Park

After several postponements, a passenger service went online in January 2018, and quickly became a symbol of Ethiopian ambition — the first stage of a planned network which, if realized, will span 3,000 miles. For tourists, it promised cheap, air-conditioned travel far from the Rift Valley scarps and rock-hewn churches of Ethiopia’s Northern Circuit, in a region that nonetheless incorporated some of the most remarkable sights in the African Horn.

‘Bring food’

The day before we intended to depart, we went to buy tickets at Lebu Station. The new line’s western terminus was a cavernous mustard-colored building topped with twin cupolas, which sat incongruously on Addis’s southwest outskirts. In the vacant ticket hall, the man at the counter seemed genuinely shocked when I asked him for two tickets to the city of Dire Dawa. Yet more disconcerting than his reaction was the sheet of paper taped to his window. Blaming recent disruptions on “local villagers,” it then issued an explicit deterrent: “Reminder: think twice before purchasing your tickets.”

The ticket vendor’s parting words: “Bring food.”

And so it was no small relief when, there the next morning, was the train at the platform. Its Chinese provenance was confirmed by the ethnicity of the “Captain” ushering people aboard, and by our salmon-colored tickets, the same as those issued by China’s National Railway.

An hour later, we were enjoying a rare sensation: swift, ceaseless movement through a sub-Saharan landscape. The train itself was a sterile beast, but the passengers had brought the atmosphere with them. The carriage full, we shared our row with a convivial family, laughing as their youngest member leaned from her mother’s arms to pilfer some of the dozen pounds of fruit we’d stockpiled in paranoid anticipation of a breakdown.

As the tiled roofs of Addis gave way to thatch, the large windows offered a moving pastoral of Ethiopian life. Yellow domes of harvested teff, Ethiopia’s national crop, ornamented the periphery of every village; boy herders stopped to watch as the train hammered by. Three hours out of Addis, the rails bisected the Awash National Park, where dust devils danced around the base of an extinct volcano, and antelope could be seen grazing on acacia trees. Local folk music tinkled from the public address system.

After all the caveats, and despite the interjection of a hapless longhorn, the train hissed triumphantly into Dire Dawa at 15:27, eight minutes ahead of schedule.

City of Djins

Despite its soporific air, Dire Dawa, effectively the railway’s midpoint, is Ethiopia’s second largest city, a fact it owes to the old French-built train line that had fallen in and out of use since its inauguration in 1917. A village backwater a hundred years ago, Dire Dawa grew over the century into a major transit hub for Ethiopian exports, not least khat, a mild herbal stimulant, which is farmed intensively in the surrounding hills. But the place we were more interested in was a 30-mile minibus ride east. The train had availed us the chance to visit the Islamic outpost of Harar.

It was discombobulating, after the prim modernity of the train, to plunge into Harar Jugol, about 120 acres of tight-knit alleyways, encircled by 15-foot walls, which is widely considered to be the fourth holiest site in Islam. We stayed in a “gegar,” a traditional Harari home which had been converted into a guesthouse, where we slept in a garret that was formerly a storage room for grain. In the adjacent main room, the owner and her friends drank thick coffee on ornate carpets. It was an oasis that belied the kaleidoscopic bustle outside.

Beyond the gegar’s wooden door, Old Harar was a treasure-house of curious museums and muftis’ shrines. But far more enticing were the streets themselves. At times, it felt like a town designed to intoxicate the senses. From the main square, our preferred route into the labyrinth was via Makina Girgir, the tailors’ road, so named for the sewing machines that line it, girgir being the onomatopoeic word for the clacking of the needles. In the spice market, drifts of dried chilies elicited sneezes from browsing shoppers, while in the meat market, bemused tourists took cover as black kites circled and dived to snatch shreds of goat from the stall-holders’ palms. In every street, walls had been enlivened by pink and blue paint to celebrate Eid.

By late afternoon, old indigents with hennaed beards filled many of the alleyways, prostrate in nests of discarded twigs. Through our young translator, Emaj, one of them complained that the price of khat was increasing. The crop had become so lucrative, its users so hooked, that the wholesalers were now increasing their prices. Drug-dealer economics 101.

At nightfall, two men headed out of the city carrying a basket of meat-scraps, then crouched in a clearing and called out into a patch of scrubland. We looked on as eight spotted hyenas emerged from the shadows to feed from their hands. Over the years, this nightly ritual has become a draw for tourists, who gather to shoot photos under the beam of car headlights. But Emaj told us it also has a more supernatural purpose: to keep the dogs close, because of the ghosts. The hyenas have their own entrances into the city, where they are said to be the only creature capable of seeing and swallowing Djins, spirits of Harar’s past inhabitants, sometimes malevolent, who stalk the alleys under cover of darkness.

Railways old and new

Before re-boarding the train for Djibouti City, we made a stop in central Dire Dawa. In the main square was the old Chemin de Fer, the railway station of the original French meter-gauge railway.

A stern woman at the entrance, suddenly all smiles once we agreed on a price for entry, donned a conductor’s cap and beckoned us in. On the train from Addis, we’d seen remnants of its ancestor running parallel to our course, sections of it buckled in the heat, others occasionally vanishing and re-emerging from the dust. Now we had found its magnificent reliquary.

Strewn over an acre of rust and rolling stock were jumbles of train components long since corroded, and decommissioned timber carriages moldering on the sidings. A giant tooling-shed, musty with dust and oil, brimmed with 50-year-old lathes. Behind it we discovered a pair of square-bodied locomotives. The conductor said we could clamber aboard, her equanimity only breaking when I succumbed to temptation and pulled a lever on the driver’s control panel. The dormant engine exhaled a long depressurizing huff and rocked on its axles. The conductor motioned that perhaps it was time to go.

Back on the new train, sitting in the hermetic carriage, it was hard not to feel nostalgic about all that old iron. Ethiopia was a place of such tangible antiquity that development invariably exacted some jarring collateral damage. I couldn’t help but ponder whether, amid the promise of economic development, the train foreshadowed something more regrettable. It seemed unlikely, for instance, that Harar’s ambient mysticism would endure once the outside world infiltrated its walls.

These were a westerner’s self-indulgent thoughts, though. I remembered how, on the first leg to Dire Dawa, I’d chatted with Aschale Tesfahun, a political science lecturer at Dire Dawa University, who’d eulogized about the train. “My life has become easier because of this train, but it’s also a major advantage for all Ethiopia,” he’d said.

I’m sure my ruminations would have reached some kind of conclusion if the train had been conducive to coherent thought. But by now our entire carriage had been taken over by Djiboutians bent on one final khat blowout before reaching home, and the resulting atmosphere left me feeling like the only sober person at a party awash with cheap cocaine. Only with sunset did the frenzied conversation subside into mere garrulousness. Mountains receded to desert, acacia to scrub, as we slid imperceptibly downhill toward the Red Sea.

A Land of Curiosities

The following day we boarded a truck, with a guide named Abdallah Ali Moussa, and barreled into the western desert. We drove for eight hours, through wastelands of rubble and Martian hills, until we arrived at a desiccated plain. Here, close to the geothermal hot spot of the Afar Triple Junction, where three tectonic plates converge, a forest of pinnacles appeared on the horizon. We had reached Lake Abbé.

At least, we had reached what used to be Lake Abbé. All that could be seen of the lake itself was a navy blur far to the north. Abdallah told us that a recent Ethiopian irrigation project on the Awash River had disrupted the lake’s inflow. The water level, always subject to seasonal fluctuations, had now retreated drastically, marooning the otherworldly landscape of limestone towers for which Abbé is famed. The scene we’d imagined, with colonies of flamingoes strutting around a topaz shore, was instead a dust bowl, friable and desolate.

Though I had to swallow some disappointment to see it, Abbé’s fumaroles, built up over millennia by the accretion of calcareous mineral deposits, still presented an astonishing panorama. In the densest areas, they formed canyons of melted wax which made me think of van Eyck’s “Last Judgment,” a ghastly ars Gothica of wailing faces. Baked from above by the sun and from beneath by geothermal activity, the ground crumbled pastry-like under our shoes.

Tomorrow, we would visit Lake Assal, Africa’s lowest point and the largest salt repository in the world, where I regret to report that I almost blinded myself when an ill-advised paddle brought my retinas into contact with water 10 times more saline than the sea. But this evening, watching Abbé’s chimneys fade to silhouettes from a simple campsite, felt like the culmination of a pilgrimage. This was the place we’d been most keen to see.

We were back on the move the next morning, fishtailing through the sand on our way to Lake Assal, when we stopped at a camp of Afar tribespeople, the nomadic pastoralists who live in the African Horn’s eastern badlands. Abdallah’s cousin lived there with his wife and seven children, and he welcomed us into his tent, a simple construction of plaited palm fronds draped over a scaffold of sun-bleached sticks.

When I emerged, blinking into the sun, a group of children had converged at the doorway. With the audience thus arrayed, the oldest one unfolded his fist to reveal some shards of obsidian he had collected. The children on either side of him smiled shyly. They wanted to show me the beautiful stones.

Somewhere across the desert, the train hurtled on. But for now, at least, modernity’s creep had far to go.