“He wouldn’t want to live like this.”

The cardiology team consulted us that Sunday evening. A patient was getting sleepy, and weak on one side.

The man was 68 years old, not a healthy man, but a strong man. He had suffered a heart attack, again, and had been transferred from another hospital. Because he’d been far from a major medical center, where a wire might have been used to clear the blockage in his coronary arteries, he was treated with the next best method, a blood-thinner, and then sent to us. The drug, tenecteplase, is an enzyme that works by digesting clots. It effectively reverses the problem and is lifesaving for a majority of patients.

But in a small minority of patients, it can also cause bleeding. Titrating the thickness of blood is precarious. If your blood is too thick you can clot. If it’s too thin you can bleed.

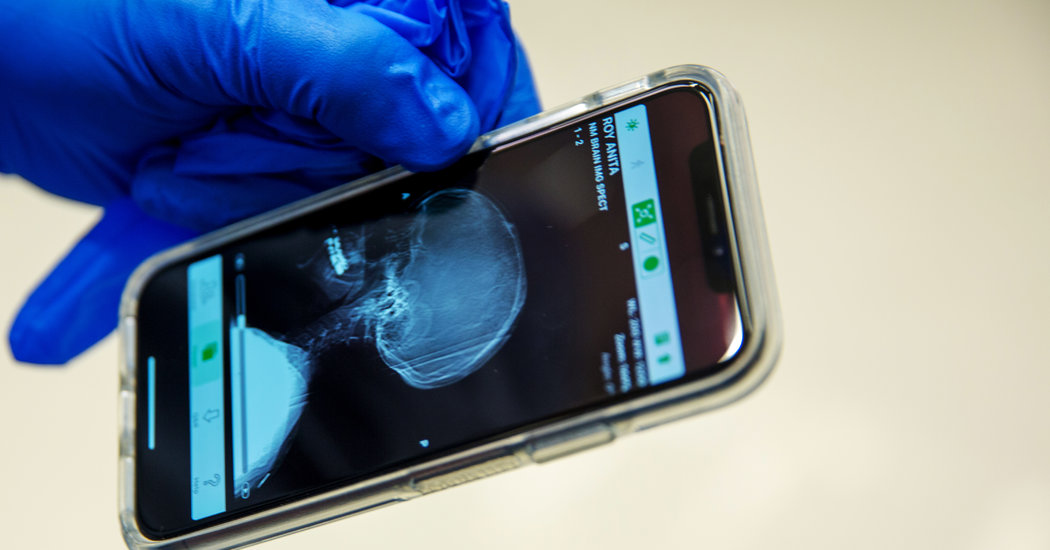

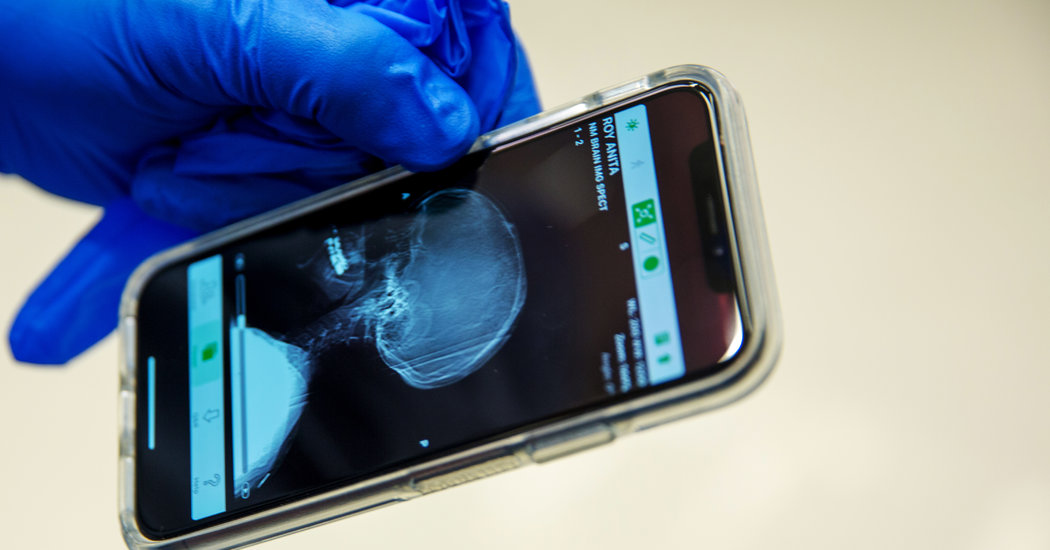

The team had performed a rapid head CT. “He’s not going to make it,” my senior whispered as I scrolled through the fresh images.

Our patient was bleeding into his brain, suffering a hemorrhagic stroke. Tenecteplase thinned his blood to save his heart, but it most likely had resulted in injury to his brain.

I ran downstairs to examine him.

He was big, and bald, and lying peacefully in his bed. With some encouragement, he gave me a grin, though lopsided. His pupils were different sizes, and half his body was paralyzed. But he was completely “there.”

I was only one month into residency. Though I knew he was critical, and I knew our next decision would be difficult, I remained optimistic.

Should we treat the ongoing heart attack, or should we focus on his latest problem? Treating his heart attack would require additional blood-thinners, which could worsen his bleed. Treating his bleed would require surgery, but going to the operating room with recently thinned blood and a frail heart is a potentially fatal prescription.

With no family present and time slipping, we had to act. Weighing our dwindling options, we took a middle road. We resolved to place an external ventricular drain.

One of the tenets of neurosurgery, perhaps the principal tenet, is the Monro-Kellie doctrine: that the cranium, the bone that encases the brain, can fit only so much. Though it affords our brains a home and remarkable protection, that comes at a cost. If its tenant gets too big, the pressure inside rises, and there’s nowhere for the brain to go but down, a harbinger of death. When our patient bled, the blood that seeped into his cranium occupied space he didn’t have.

We can try to treat this pressure medically, but in an emergency like this, the definitive treatment is to place an external ventricular drain. Since the French surgeon Claude-Nicolas Le Cat first performed it in 1744, placing this fine tube into the brain has been used as a swift and durable way to drain some of the cerebrospinal fluid that buoys and nourishes the brain, creating space and relieving pressure.

It was my job to place it.

We calmed and sedated him, his cardiac monitor periodically reminding us of his starving heart muscle. I carefully shaved the little hair he had. I scrubbed his scalp with a soapy sponge, cleaned it with rubbing alcohol, and painted it with bactericidal iodine. The room was soon clad in hospital blue drapes, with him at the center, a light illuminating his crown. The light beamed hot over my mask and gown.

As I cut into his scalp, his blood spilled forth, as thinned blood does. That familiar scent immediately filled my nostrils. I scraped away the subcutaneous tissue revealing his ivory white cranium. I started drilling a hole, to break the cerebral seal we are all born with. Once through, I cut his dura mater, the rubbery sheath of tissue that encases the brain. He was now exposed. Using external anatomic landmarks as my guide, I gently passed the tube into his brain. You can’t help but to notice the brain’s jellylike consistency.

Crimson cerebrospinal fluid gushed out. Success.

With such insults to the brain, it isn’t as much a race against time. Yes, time is tissue. But really, this was a race against space. He now had a little more room to suffer his bleed.

I sutured the tube into place, and closed his incision. We took him upstairs to the neurological intensive care unit. Between his brain and his heart, the former was the priority. Remarkably, his heart never stopped beating.

Later that evening, his family and friends trickled into the unit to visit him. “What are his chances?” is always the first question. It was difficult to be certain, but his prognosis was poor. Even with our best efforts, he was now comatose, reacting very little to the world around him.

The brain is an expansive architecture of neurons and glia that communicate with one another to generate the “self.” Some parts of the brain allow us to sense the world around us: light, sound, touch, temperature, taste, smell, position, vibration, pain. Others allow us to go forth into the world, through motion, through voice. Still more make decisions, form memories, generate emotions. As space became scarce, many parts of this network had failed. And ultimately, he had lost his ability to awaken.

I think I had been the last person to speak to the patient before he had drifted into a coma. “What’s your name?” I had asked him. “Squeeze my finger. Wiggle your toes,” I prodded. He had responded but had grown sleepier with each request.

Over the next few days, our team met repeatedly with his family members. They eventually agreed on a decision: “He wouldn’t want to live like this.”

We aligned our efforts to match what they thought would be his wishes, and instead focused solely on his comfort.

Within the hour, he died.

I’m early in my training. Maybe I should have known better and expected this. My senior did. Our patients are some of the sickest in the hospital. I know this well, and it is part of what attracts me to this field. However, the extent of this reality doesn’t fully hit you until you’re talking to the family, to the people who love your patient. I have a feeling I’ll be more realistic going forward.

Neurosurgery is a nascent field, with new uncertainties at every corner. Some are less taxing than others.

Dr. Abdul-Kareem Ahmed is a neurosurgery resident at the University of Maryland Medical Center.