Huddled on a chaise on the upper deck of the Orient, the dahabiya that I had chosen for a cruise down the Nile, I sipped hibiscus tea to ward off the chill. Late in February, it was just 52 degrees in Aswan, where I had boarded the sailboat, but the scenery slipping past was everything the guidebooks had promised: tall sandbanks, curved palms and the mutable, gray-green river, the spine of Egypt and the throughline in its history.

Valley of the Kings

The Temple of

Horus at Edfu

Street data from OpenStreetMap

Gebel

el-Silsila

saudi

arabia

Temple of

Kom Ombo

I’d been obsessed with Egypt since childhood, but it took a cadre of female adventurers to get me there. Reading “Women Travelers on the Nile,” a 2016 anthology edited by Deborah Manley, I’d found kindred spirits in the women who chronicled their expeditions to Egypt in the 19th century, and spurred on by them, I’d planned my trip.

Beside my chair were collections of letters and memoirs written by intrepid female journalists, intellectuals and novelists, all British or European. Relentlessly entertaining, the women’s stories reflected the Egyptomania that flourished after Napoleon invaded North Africa in 1798. The country had become a focal point for artists, architects and newly minted photographers — and a fresh challenge for affluent adventurers.

Their dispatches captured Egypt’s exotica — vessels “laden with elephant’s teeth, ostrich feathers, gold dust and parrots,” in the words of Wolfradine von Minutoli, whose travelogue was published in 1826. And they shared the thrill of discovery: Harriet Martineau, a groundbreaking British journalist, feminist and social theorist, described the pyramids edging into view from the bow of a boat. “I felt I had never seen anything so new as those clear and vivid masses, with their sharp blue shadows,” she wrote in her 1848 memoir, “Eastern Life, Present and Past.” The moment never left her. “I cannot think of it without emotion,” she wrote.

Their lyricism was tempered by adventure: In “A Thousand Miles Up the Nile,” Amelia Edwards, one of the century’s most accomplished journalists, described a startling discovery near Abu Simbel: After a friend noticed an odd cleft in the ground, she and her fellow travelers conscripted their crew to help tunnel into the sand. “Heedless of possible sunstroke, unconscious of fatigue,” she wrote, the party toiled “as for bare life.” With the help of more than 100 laborers, supplied by the local sheikh, they eventually descended into a chapel ornamented with dazzling friezes and bas reliefs.

Though some later took the Victorians to task for exoticizing the East, these travelers were a daring lot: They faced down heat, dust, floods and (occasionally) mutinous crews to commune with Egypt’s past. Liberated from domestic life, they could go to ground as men did.

Wolfradine von Minutoli wrote of camping out under the stars by the pyramids. Florence Nightingale, then 29 and struggling to gain independence from her parents, recalled crawling into tombs illuminated by smoking torches. Nightingale, among others, was struck by the otherworldliness of it all. Moved by the fragmented splendor of Karnak, the sacred complex in Luxor, she wrote to her family, “You feel like spirits revisiting your former world, strange and fallen to ruins.”

Taken with their sense of adventure, I wanted to know whether the Nile journey had retained its mystique. Would I feel the presence of these women along the way? And could modern Egypt rival the country that they encountered?

As in the Victorian era, there would be unknowns: Political upheavals and terrorist activity are realities in Egypt. The country’s tourist industry reached a nadir after the 2015 attack on a flight from the seaside resort of Sharm el Sheikh; more than 200 people perished.

Violence has continued to flare: In December, a bomb destroyed a tour bus near the pyramids in Giza, killing four people. A second bus bombing in May injured at least 14.

But risk, I decided, is relative. The State Department’s advisory places Egypt at Level 2 out of 4 (“exercise caution”), along with China, Italy and France. And though still fragile, the country’s travel industry (which recorded 11 million visitors last year, up from 5.4 million in 2017) is rebounding.

Aboard the Orient

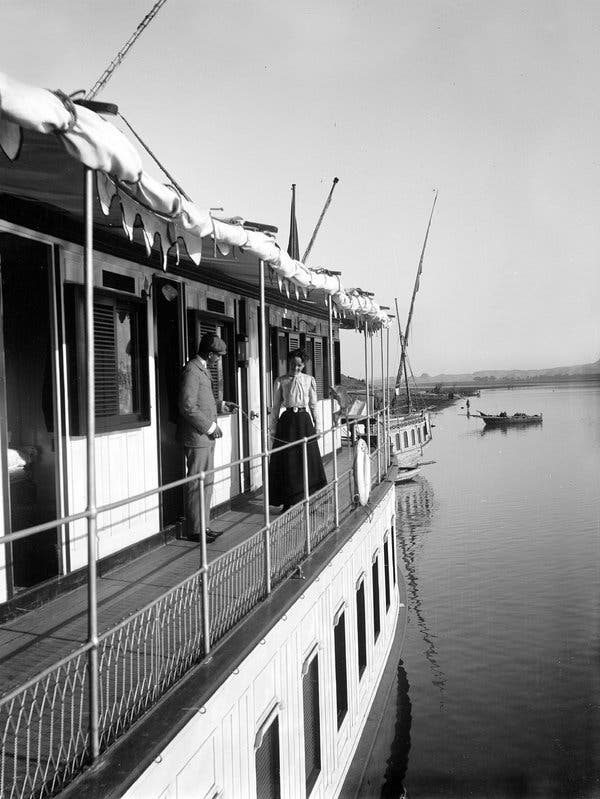

Dozens of double-masted dahabiyas and river cruisers now ply the Nile, but I was drawn to the low-key Orient — a charming wooden sailboat, it has a capacity of 10 people but I was joined by only four. Instead of a cinema and floor shows, we had backgammon and intermittent Wi-Fi. (The cost of the three-day cruise, including my single supplement, was $964.) On the upper deck, I could lounge on oversize cushions and watch storks skim the river. In the salon, a low sofa and carved armchairs were perfect for dipping into vintage National Geographics.

My cabin was compact, with twin brass beds and floral wallpaper. The river was close; I could have pulled aside the screens and trailed my fingers through the current. (Not that I did; early travelers praised the “sweetness” of Nile water, but trash bobs on its shores and bilharzia, a parasitic disease that attacks the kidneys, liver and digestive system, is a risk.)

Before 1870, when the entrepreneur Thomas Cook introduced steamers (and declassé package tours), a cruise on the world’s longest river was a marathon. Journeys lasted two or three months and typically extended from Cairo to Nubia and back.

Just getting on the river was a trial: After renting a vessel, travelers were obliged to have it submerged to kill vermin. The boats were then painted, decorated and stocked with enough goods to see a pharaoh through eternity.

Published in 1847, the “Hand-book for Travellers in Egypt” advised passengers to bring iron bedsteads, carpets, rat-traps, washing tubs, guns and staples such as tea and “English cheese.” Pianos were popular additions; so were chickens, turkeys, sheep and mules. M.L.M. Carey, a correspondent in “Women Travelers on the Nile,” recommended packing “a few common dresses for the river,” along with veils, gloves and umbrellas to guard against the sun.

With my fellow passengers, I spent the first afternoon at a temple near the town of Kom Ombo. The structure rose in the Ptolemaic period and was in ruins for millenniums. Mamdouh Yousif, our guide, talked us through it all. A native of Luxor, he used a laser pointer to pick out significant details and served up far more history than I could absorb.

Celebrated for its majestic setting above a river bend, the temple was nearly empty. Reggae music drifted from a cafe and shrieks rose from a neighborhood playground.

Dedicated to Horus, the falcon god, and Sobek, the crocodile god, Kom Ombo has a separate entrance, court and sanctuary for each deity. Inside are two hypostyle halls, in which massive columns support the roof. Each hall was paved with stunning reliefs: Here was a Ptolemaic king receiving a sword; there, a second being crowned. A mutable figure who was both aggressor and protector, Sobek was worshipped, in part, to appease the crocodiles that swarmed the Nile. Next to the temple, 40 mummified specimens — from hulking monsters to teacup versions — are enshrined in a dim museum, along with their croc-shaped coffins.

Defaced by early Coptic Christians, damaged by earthquakes and even mined for building materials, Kom Ombo was in disrepair until 1893, when it was cleared by the French archaeologist Jean-Jacques de Morgan. Now, it’s inundated in the late afternoon, when cruise-boat crowds arrive. As we were leaving, folks in shorts and sunhats just kept coming, fanning out until the complex became a multilingual hive.

Back on the Orient, my cabin grew chilly and I wished, briefly, that I had made the journey in the scorching summer. An early supper improved my mood, as did the winter sun setting behind silvery-gray clouds. Since I’d brought a flashlight, I was only mildly annoyed when we learned that our generator would stop at 10 p.m. The darkness was nearly complete, but silence never set in: Creaks, thumps and splashes resounded through the night.

In the morning, we headed north to the sandstone quarry and cult center of Gebel Silsila. With their rock faces still scored with tool marks, the cliffs have an odd immediacy — as if armies of stonecutters could reappear at any moment.

The compelling part of the site is a hive of rock-cut chapels and shrines. Dedicated to Nile gods and commissioned by wealthy citizens, they are set above a shore lined with bulrushes. Eroded but evocative, some retain images of patrons and traces of paintings.

In Edfu, an ode to power in stone

After lunch, we traveled downriver to Edfu, to Egypt’s best-preserved temple. Tourism has made its mark in the agricultural town: Cruise boats line the quay, and the drivers of the horse-drawn carriages known as calèches stampede all comers. Begun in 237 B.C. and dedicated to Horus, the temple was partially obscured by silt when Harriet Martineau visited in 1846. “Mud hovels are stuck all over the roofs,” she wrote, and “the temple chambers can be reached only by going down a hole like the entrance to a coal-cellar, and crawling about like crocodiles.” She could see sculptures in the inner chambers, but “having to carry lights, under the penalty of one’s own extinction in the noisome air and darkness much complicate the difficulty,” she wrote.

Excavated in 1859 by the French Egyptologist Auguste Mariette, the temple is an ode to power: A 118-foot pylon leads to a courtyard where worshippers once heaped offerings, and a statue of Horus guards hypostyle halls whose yellow sandstone columns look richly gilded.

Feeling infinitesimal, I focused on details: a carving of a royal bee, an image of the goddess Hathor, a painting of the sky goddess Nut.

Mr. Yousif kept us moving through the shadowy chambers — highlighting one enclosure where priests’ robes were kept and another that housed sacred texts. Later I thought of something Martineau had written: “Egypt is not the country to go to for the recreation of travel,” she said. “One’s powers of observation sink under the perpetual exercise of thought.” Even a casual voyager, she wrote, “comes back an antique, a citizen of the world of six thousand years ago.”

Our dinner that night was festive: When someone asked for music, our purser, Mostafa Elbeary, returned with the entire crew. Retrieving drums from an inlaid cabinet, they launched into 20 exuberant minutes of song.

The night quickly deteriorated, however. Gripped by an intestinal upheaval, I bumped my way back and forth to the bathroom. In the morning, I was too ill to visit more tombs and temples. The chef sent me soupy rice, and Mr. Elbeary kept me supplied with Coke.

Watching the river in bed, I realized what was missing: While 19th-century voyagers rode camels into the desert and ventured into villagers’ homes, we had seen little of local life. Before the cruise, I had sampled the chaos in Egypt’s capital. With a guide from the agency Real Egypt, I spent an afternoon exploring the neighborhood known as Islamic Cairo. Heading down a street lined with spice stalls and perfume shops, we had passed Japanese children with sparkly backpacks, Arab women chatting into cellphones tucked into their hijabs and old men arguing in cafes. We stopped to watch Egyptian girls draping themselves in rented Scheherazade costumes; after snapping selfies, they happily vamped for me.

A trip to Giza was nearly as diverting. Though I didn’t find the monuments inspiring — the Pyramids looked like stage flats against the searing-blue sky — others did. I was standing by the Sphinx when I overheard a man angling his phone toward its ravaged face. “You see me?” he asked, ducking in front of the camera. “That’s the Sphinx. It’s one of the most famous monuments in the world.”

Roman emperors and Egyptian gods

The next day I roused myself for our final outing. We had docked at the town of Esna, and from my window I watched an ATV driven by a boy who looked to be about 7 just miss a herd of goats.

The others were waiting, so I followed Mr. Yousif through the streets at warp speed. Built during the reign of Ptolemy V and dedicated to a river god, Esna’s temple was conscripted by the Romans and then abandoned. Only its portico had been excavated when Nightingale visited. In a letter to her family, she said, ”I never saw anything so Stygian.”

Now partly reclaimed, the temple is 30 feet below street level. Beyond the portico is a hypostyle hall whose columns are inscribed with sacred texts and hymns. Still traced with color, they blossom into floral capitals. On the walls are images of Roman emperors presenting offerings to Egyptian gods.

On our way back to the boat, Mr. Yousif led us through narrow streets where children were racing about. Two little girls, one in a bedraggled party dress, followed us, whispering. A succession of boys darted into our paths to say, “Welcome, hello, hello.” From a closet-size barber stall, three men called out; a merchant in another stall held up his tortoiseshell cat.

Exploring Luxor’s riches

After a celebratory breakfast the next day — crepes, strawberry juice, Turkish coffee — our cruise ended. A driver from the dahabiya company was waiting to take us to Luxor, about an hour away.

Though it was little more than an expanse of fields dotted with mud huts, in the early 19th century, dahabiyas made lengthy stops in Luxor. Near the town is one of the world’s largest sacred monuments and across the Nile is the Valley of the Kings.

In the afternoon, I set out for Karnak. Founded chiefly by Amenhotep III and originally dedicated to Amon-Re, the complex was modified and enlarged by rulers, including Ramses II.

In the 19th century, its pylons, halls and courts were still mired in detritus: Nightingale was unsettled by the temple’s “dim unearthly colonnades” when she visited on New Year’s Eve in 1849. “No one could trust themselves with their imagination alone there,” she wrote. With enormous shadows looming, said Nightingale, “you feel as terror stricken to be there as if you had awakened the angel of the Last Day.”

Though it’s now besieged by tourists, the complex is still haunting. An avenue of ram-headed sphinxes leads to an imposing first pylon; beyond is a hypostyle hall where 138 pillars soar into empty space.

Wandering without a guide, I lingered over details: the play of light on a broken column; the base of a shattered statue that had left its feet behind. On the way to the necropolis across the river, I thought about the desecration described by Victorian travelers. Jewelry, cartouches and body parts were all on the market, and Amelia Edwards, author of “1,000 Miles Up the Nile,” was among those who were offered a mummy.

After casually expressing an interest in an ancient papyrus, wrote Edwards, she and a companion had been “beguiled into one den after another” and “shown all the stolen goods in Thebes.” Inevitably, they found themselves underground with a crumbling object in “gaudy cerements.” (She rejected it.)

Sheltered by limestone cliffs and set off by a limitless sky, the Valley of the Kings has been brought to order: Vendors now sell their wares in a visitors’ center, and tourists can hop an electric train to the burial grounds.

One of the most spectacular tombs in the royal warren belonged to Seti I; it was known to Victorians as “Belzoni’s tomb.” The entrance was breached in 1817 by the Italian adventurer Giovanni Belzoni who removed the sarcophagus of Seti I and sold it to a collector. In 1846, Martineau visited the chamber that had held the sarcophagus and reported, “We enjoyed seeing the whole lighted up by a fire of straw.” With its brilliant paintings set off by the flames, she said, “it was like nothing on the earth.”

It still is: The deepest and longest tomb in the necropolis, the resting place of Seti I is adorned with astonishing reliefs. Scenes from texts, including the Book of the Dead, lead from one spectacular enclave to another. On the day I visited, the crowds were elsewhere and the silence was profound.

The pharaoh who eluded the Victorians, of course, was Tutankhamun. Cloaked in obscurity for 3,000 years, his tomb was unsealed by Howard Carter at a time when the valley was believed to hold no surprises. In January, conservators completed nine years of restoration that revived the intimate enclosure.

Though most of Tutankhamun’s treasures are in the Egyptian Museum, his outer sarcophagus is still in the burial chamber. Stripped of its bandages, his corpse, blanketed in linen, now lies in a glass box — a desiccated figure blanketed in linen. Only his blackened head and feet are exposed, but he looks exquisitely vulnerable.

Surrounding the remains of the boy king are murals depicting him as a divinity; he enters the afterlife in the company of Anubis and Osiris and Nut. Set against a gold background, the images temper the pathos of his remains.

In the end, the tomb lost for so long is a reminder that in Egypt, the past continues to evolve. Perspectives can shift; voices can change. And something astonishing may be just around the corner.

Michelle Green has written for The Wall Street Journal, The Washington Post, The New York Review of Books and other publications. She is the author of “The Dream at the End of the World: Paul Bowles and the Literary Renegades in Tangier.”