One Monday afternoon in mid-August, the megalopolis of São Paulo, Brazil, fell into darkness.

The cause could have been forest fires burning more than a thousand miles away in the state of Rondônia, but the miasma could have stood as a metaphor for the way the country’s president, Jair Bolsonaro, has cast a shadow in his nine months since taking office: increasing deforestation, using polarizing rhetoric and seeming to promote homophobia and transphobia.

That same day, Juliano Corbetta, an editor, said he was sitting in his São Paulo apartment, looking at a photograph of a male model wearing only a diamanté-studded thong (with a rhinestone heart applied to the model’s right buttock, for flair). Mr. Corbetta was evaluating the image for inclusion in his new publication, Samba Zine, which features only L.G.B.T.Q. Brazilian individuals, communities and causes.

Samba Zine is also produced by L.G.B.T.Q. Brazilian photographers, stylists, makeup artists and more. The magazine will be released in late September, will then publish twice a year, and will initially come with a footwear and T-shirt collaboration with the Brazilian brand Fiever, with proceeds from the items going to a São Paulo L.G.B.T.Q. support group called Casa 1.

“Samba is a visual manifesto,” Pedro Pedreira, a photographer who contributed to the debut, wrote in an email. “It documents Brazilian queer culture, right now, and in this moment of political calamity, I think it gives us some hope. The fashion, and a hint of sexiness, gives us the fantasy we need in these dark days.”

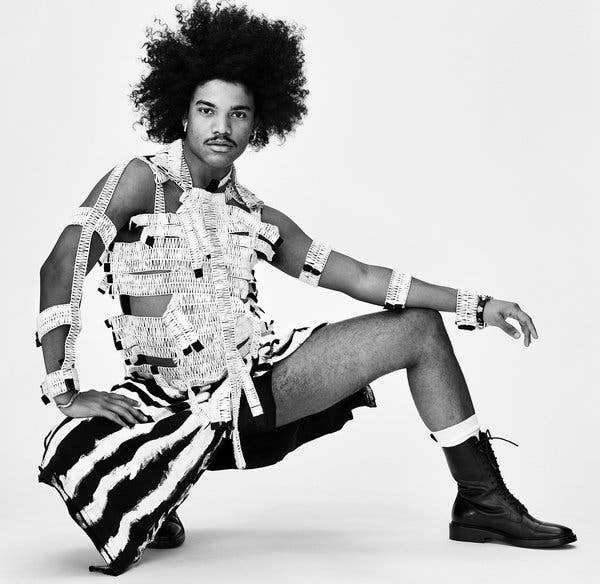

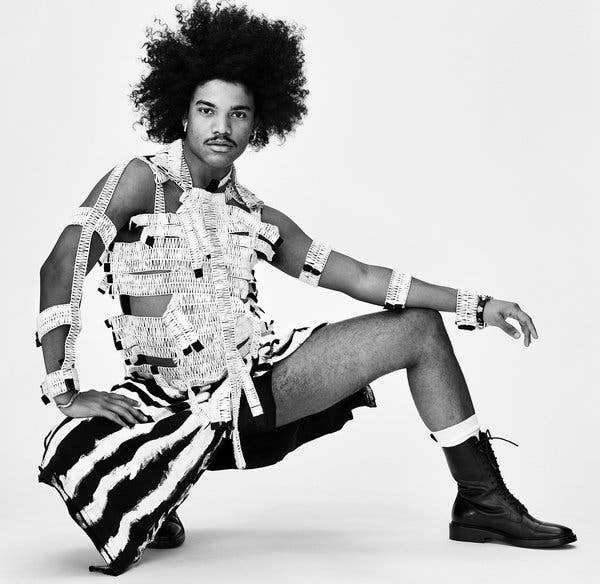

While Samba Zine has fashion-driven editorials (brands shown are not solely Brazilian) and is beautifully produced, its real gravity springs from its sense of openness and optimism. Many compositions show subjects with relaxed, smiling dispositions, including the gay artist Samuel de Saboia, the bisexual actor Pedro Alves and the transgender singer Liniker.

“For me, it was a moment with my girls,” Liniker said in an audio message. “Celebrating our life and showing that we are alive.” There is skin, but it is far from suggestive.

Mr. Corbetta, 40, founded Made in Brazil, a popular blog turned magazine that celebrates the Brazilian male physique. “The idea for this started almost two years ago,” he said in a phone interview, referring to Samba Zine. “I wanted to create a fashion vehicle with a queer voice in Brazil, because it did not exist.”

“As time passed,” he continued, “the project has become more of a response to the political climate in the country. Essentially, Samba Zine has evolved to become a book about a rising queer, and especially a black and queer, movement in Brazil. The subjects range from established artists and musicians to people we cast on Instagram.”

This energized counter-establishment movement is on full display at a party called Batekoo, which was started in 2014 in the state of Bahia by Mauricio Sacramento and Artur Santoro, who are D.J.s and producers. They described the party as “a safe space for minorities in general to express themselves through culture, black music, dance and aesthetics.”

Mr. Sacramento and Mr. Santoro are featured in Samba Zine, in a story that was photographed in late August at New York City’s Afropunk festival. They now hold their events in Salvador, São Paulo, Rio de Janeiro, Recife and Belo Horizonte, and have also expanded internationally because, they said in an email, “aesthetics are not detached from politics. Occupying one’s own body is the first step in occupying new social spaces. By this, we mean building the self-esteem of communities that have been subjectively molded out of self-hatred.”

Though there is a palpable momentum behind queer Brazilians’ expanding presence and visibility, there were roadblocks to Mr. Corbetta’s vision of celebrating them in glossy pages in a country with a history of racism, homophobia and transphobia.

More than a few subjects dropped out at the 11th hour, perhaps nervous about blowback for appearing in a queer-centric project. Mr. Corbetta said this was part of it, but that the trepidation is overarching. “Unless there are more people that are publicly out there, there will always be fear,” he said.

“On one side, you have people that are not necessarily in a position of mainstream power, and these are the people that are fighting for change and for rights,” he said. “On the other, you have those that are more mainstream, but these people, generally speaking, do not take stands. They don’t make their gayness visible. It’s O.K. to be out, but it’s rare for someone to be out and outspoken about it.”

Samba Zine, whose first issue is 200 pages, has no advertising, in the traditional sense. Instead, brand partners, including Luxottica and the Brazilian underwear label Mash, provided funding and their products are featured “organically” in photo spreads.

Mr. Corbetta said that he was not given any restrictions from the brands (though he did note that in meetings where he is seeking sponsorship, he will often be asked “‘How gay is this going to be?’ That question needs to go extinct,” he said).

Mr. Alves, the actor, said in an email that “there are ad campaigns in the country with gay couples, trans individuals, drag queens. This would have been unthinkable years ago. Companies know the importance of ‘pink’ money.” There is a slowly growing nationwide acceptance, but, statistically, Brazil remains a dangerous place for L.G.B.T.Q. people.

Brazil’s Supremo Tribunal Federal ruled in June to include homophobia and transphobia as part of the country’s policies that outlaw racism. This came after the gay rights association Grupo Gay da Bahia, the oldest of its kind in the country, reported 420 community deaths by homicide or suicide in 2018.

Well over 100 queer Brazilians have been murdered in 2019. Marielle Franco, a lesbian councilwoman in Rio de Janeiro, was the victim of a high-profile 2018 assassination that still has the city roiling. Samba Zine, and its message, may be a hard sell beyond its immediate audience.

Ultimately, Mr. Corbetta’s goal is to help educate through his medium. “I am a gay man, I am 40 years old, and I recognize that I am in a position of privilege,” he said. “I want for the kids in this country to see that there’s a community. I want them to feel inspired and embraced. To know we’re here, when they’re hearing hate speech from the government.”