Peering inside cells has been an integral part of biology ever since the 17th century, when cells were discovered under a microscope. But even with advances in light and electron microscopy, researchers who want to understand where various molecules are inside a cell — and thus how cells like neurons, immune cells and tumors differ from one another — can glean only so much.

Now, scientists have come up with a new way to capture what’s going on in there. The approach, called DNA microscopy, uses simple chemical reactions essentially to map a cell’s interior, highlighting the contents and indicating exactly where everything can be found.

The technique, described Thursday in the journal Cell, also reveals a wealth of genetic information not accessible with traditional microscopy tools: which immune receptor genes are turned on or off, say, and whether cells are healthy or full of disease-causing mutations.

“DNA microscopy captures both genetic and spatial information simultaneously,” said Joshua Weinstein, a postdoctoral researcher at the Broad Institute of M.I.T. and Harvard and the lead author of the paper. “That’s what’s really beautiful about it.”

[Like the Science Times page on Facebook. | Sign up for the Science Times newsletter.]

A scientist starts by pipetting readily available chemical reagents onto a sample. This causes small, synthetic DNA tags to latch on to biomolecules inside the cells. A subsequent reaction leads each tag to generate copies, which emanate outward like radio signals from a cellphone tower.

Cellphone companies determine the locations of users through triangulation: identifying where the signals from three or more cell towers intersect. DNA microscopy works similarly, effectively mapping the location of every molecule by noting where the boundaries of the various tags overlap.

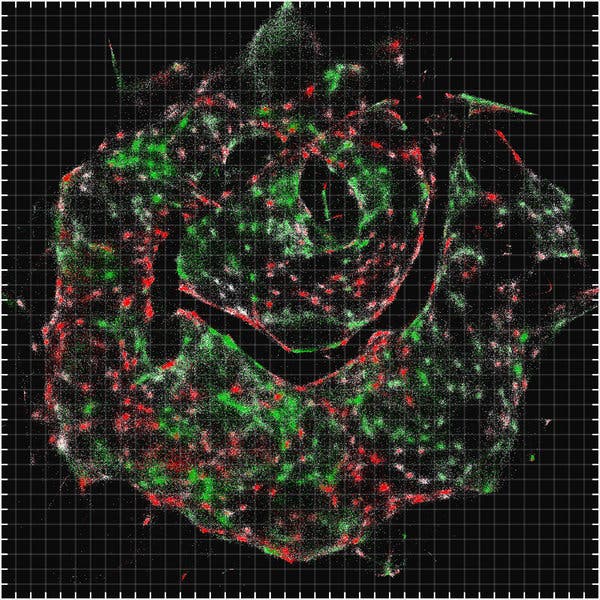

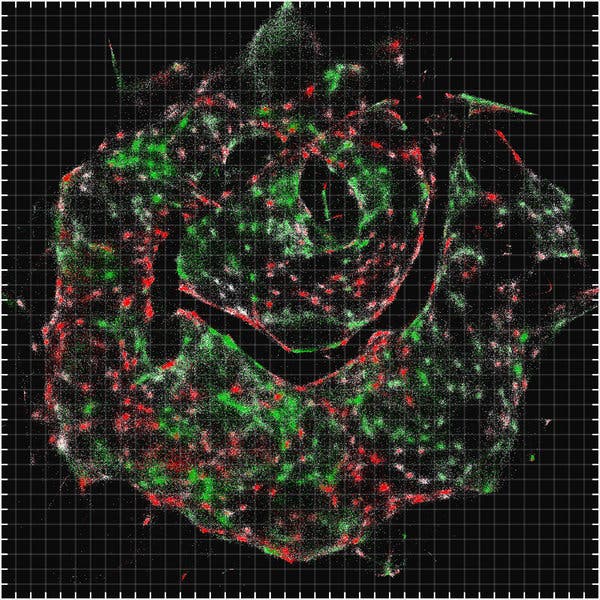

CreditJoshua Weinstein/Broad Institute

In the end, all the DNA is collected, sequenced, and put through a computer program that reconstructs the locations of the original molecules.

“It’s a completely new way of visualizing biology,” Dr. Weinstein said. Because the technology uses tagged molecules within the cells to see how things are naturally arranged in samples, scientists can “see the world through the eyes of the cell,” he said.

With DNA microscopy, scientists could map any group of molecules that will interact with synthetic DNA tags — cellular genomes, RNA and proteins.

“The first time I saw a DNA microscopy image, it blew me away,” said Aviv Regev, a biologist at Broad and the Howard Hughes Medical Institute.

DNA microscopy accurately recreated where green- and red-tagged messenger RNA, used to translate instructions from the genome, was located in a sample of human breast cancer cells. It also showed that the sequences of some of the RNA molecules varied slightly from one another, something that other imaging techniques can’t do, she said.

Recent advances in microscopy have allowed scientists to view the minute spatial details of cells by beaming electrons through them or blowing cells up like balloons. The advantage of DNA microscopy is that it combines spatial details with scientists’ growing interest in — and ability to measure — precise genomic sequences, much as Google Street View integrates restaurant names and reviews into outlines of city blocks.

Because the technique uses quick chemical reactions to collect and integrate information, rather than light or electrons, it can process large numbers of samples. It can also be done with less specialized and less expensive equipment; all that’s needed is a set of standard chemicals and a DNA sequencer.

Calling it microscopy may be a misnomer. “The researchers didn’t use any kind of microscope,” said Ulrike Boehm, an imaging expert at the Howard Hughes Medical Institute’s Janelia Research Campus in Ashburn, Va., who was not involved in the study. “What the researchers did is more like DNA mapping.”

Still, Dr. Boehm said, “This is very powerful technology.”