Savagnin blanc — not to be confused with the sauvignon blanc the sommelier recommended with your cheese course — is a fruity, acidic grape from the vine-encrusted hills of Jura, near France’s border with Switzerland. And if you visit and sip the region’s white wines today, you’ll be tasting the exact same grape, down to the genetic level, that has gone into its wines for at least 900 years.

“It’s kind of frozen in time,” said Nathan Wales, an archaeologist at the University of York in the UK and the lead author of the paper, published Monday in the journal Nature Plants. “I had assumed that they were just recycling the names, and lineages would come and go, but we can see that’s not the case.”

[Like the Science Times page on Facebook. | Sign up for the Science Times newsletter.]

The study followed an analysis of the DNA of 28 grape seeds found in wells and latrines at various archaeological sites in France, where crushed wine grapes were dumped, or simply excreted by animals or people who ate them. Dr. Wales’s team then compared those sequences to GrapeReSeq, a genetic bank for contemporary wine grapes.

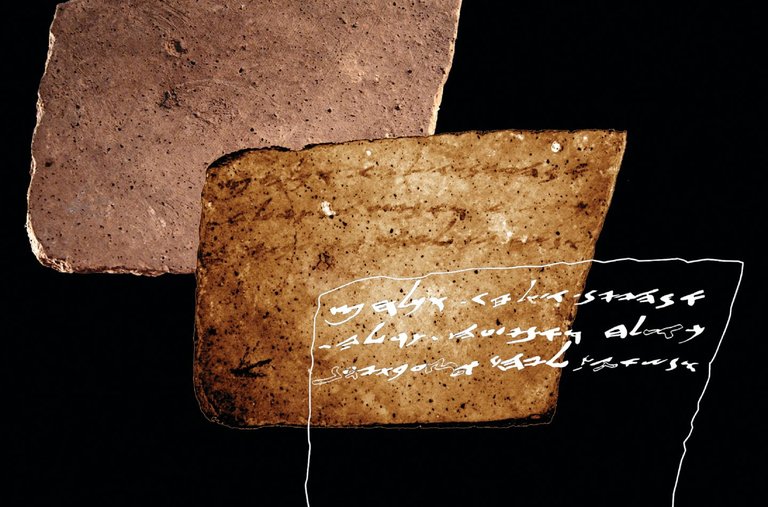

Grape seeds found by archaeologists in France.CreditLaurent Bouby, CNRS/ISEM

Their findings reinforce how winemakers can devote centuries, if not millenniums, of loyalty to certain varieties of grapes. Faced with the choice of letting nature takes its course and allowing new grape varieties to develop, or sticking with a reliable fruit by grafting vines to create perfect clones, most growers have spent the last 10 or 20 centuries learning how to better produce what works.

The new DNA results are consistent with historical records, which had suggested viticulture in this region goes back at least 2,000 years. Back in the first century, when Roman vineyards dotted southern France, Pliny the Elder described 91 grape varieties. He also described the grafting technique still commonly used for cloning grapevines. But it hasn’t been easy to link the Roman names he used to current vines.

Dr. Wales’s team found continuity that might reach back to Pliny’s age.

In La Madeleine, a church complex in the city of Orleans, a seed found in almost a thousand year-old cesspit turned to be an exact match for modern-day savagnin blanc.

Other seeds seemed to be separated from their contemporary relatives by only one reproductive cycle in almost two millenniums. One seed found in a first-century Roman well was closely related enough to have shared a parent with Pinot Noir grapes, for example. Three more seeds in a second-century pit were related in the same way to Syrah grapes.

In addition to quaffing wines very similar to modern-day Pinot and Syrah, the Romans also must have transported varieties they liked over large distances, as historians have long believed. The closest relative to one seed, found near the coast of southern France, is now grown solely in the Alps.

In the future, Dr. Wales says, looking into the lineages of even more ancient seeds could help breeding efforts. Plus it could help test how long local agricultural traditions really go back.

“It’s pretty cool that when you lift a glass of savagnin blanc today, the genetic identity of the wine in your glass is identical to something that was being drunk so long ago,” said Sean Myles at Dalhousie University in Canada, who led an earlier genetic study of over a thousand modern wine grapes but was not involved in the current study.

This past weekend, to celebrate the study’s forthcoming publication, Dr. Wales bought a bottle of Gewürztraminer, a pink-hued savagnin blanc relative that was easier to get outside of France.

“It was delicious,” he says.