I.

My mother, Vivian Jarrett-Irving, is the owner of two fur coats: a full-length mahogany mink and a fox that hits right below the knee. Both hang from pegs she affixed to the back wall of her bedroom closet, as if their sensual, febrile glamour were too singular to be slotted in among the racks of common clothing.

But their storage is purely sensible. “I keep them in here because it’s cooler,” she said. Kept too warm, the pelts will shed, and excessive humidity may rot the underlying skins; too cold and the hides are prone to dry out and crack. Both must be routinely brushed and shaken out. From Easter until the first cold days of winter, the coats are kept in a vault at Saks Fifth Avenue. There, for $175 per annum, the ideal temperature (under 55 degrees Fahrenheit, 50 percent humidity) is fastidiously maintained.

We spoke at home in Chicago in January, on a night when the coats were newly home for the season. My mother was readying for bed. Her long hair was wrapped, her last cigarette of the night lit, and she was watching the evening news, waiting to hear whether the days ahead would bring snow and, with it, the opportunity to wear fur. “We grew up poor,” she said to me, though I’m plenty familiar. “We didn’t have a lot, but we always looked nice. I think black people, in general, no matter their incomes, like to look nice.”

My mother purchased her first fur some 15 years ago, when she was a single woman, employed at the drug rehabilitation center she credits with her own sobriety. “I saved some for a down payment, then paid the rest off over three, maybe four years with an installment plan — a layaway,” she said. The second coat, the fox, was an anniversary gift from her husband, also a longtime fur wearer, whom she married in 2010.

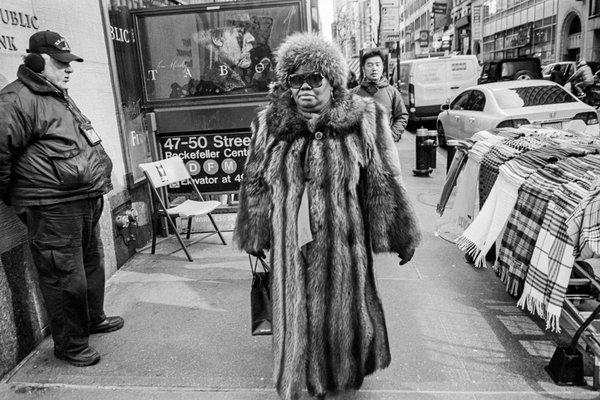

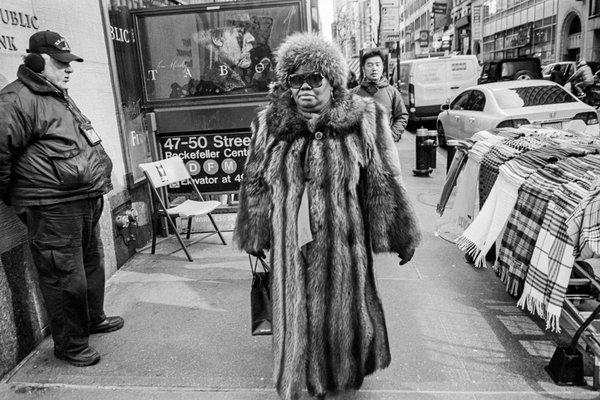

New York City, 2019.CreditAndre D. Wagner for The New York Times

My mother likens caring for the coats to the attention her own mane requires. Chemically, there is little difference between fur and hair. Mammals that are not primates are said to have fur, while hominids (humans, chimps, orangutans) have hair. As the least hirsute primates, humans have long sought out furred animals — trapping, killing and skinning them — for the purpose of wearing them. In “Fur, Fortune, and Empire,” the historian Eric Jay Dolin goes back to the Bible: Upon banishing Adam and Eve from Eden, he writes, God provided them with “garments of skins” to cover their nakedness.

These days there are plenty of other materials available to cover one’s nakedness, a point that anti-fur activists readily make. The past few decades have seen a humanitarian backlash to animal fur clothing. Major fashion designers, including Gucci, Stella McCartney and, most recently, Chanel, have forsaken it; several cities in California, including Los Angeles and San Francisco, have banned sales of the material.

But there is a sense among many black women that this broader, cultural disavowal of fur has coincided with our increased ability to purchase it. (Or as Paula Marie Seniors, a historian and professor of Africana studies at Virginia Tech, reported her mother saying: “As soon as black women could afford to buy mink coats, white society and white women said fur was all wrong, verboten, passé.”) For women like my mother and grandmother, my aunts and my sisters, a fur coat is more than a personal luxury item. It is an important investment.

My grandmother, Lucille Bones-Jarrett, was born in 1931 in Holly Grove, Ark., and migrated to Chicago at the age of 15, already a mother to one boy: two souls among six million black migrants who were propelled north by the tenuous hope of something better. Like many other émigrés of the Great Migration, my grandmother spent most of her life in a housing project. She raised nine children there.

“My mother never owned a house. She couldn’t afford it,” my mother said. “And even if she’d had the money, they wouldn’t have let her have one.” Federal housing codes that barred fair loans from being offered to black people, as well as other forms of housing discrimination, rendered homeownership impossible for many black families, and arduous for those who could attain it. So money was put toward other markers of personal prosperity, the kind that retained value and could be passed down to the next generation. “My mother never had a house,” my mother said again. “But she had fur.”

II.

A lot of North American history can be told in fur.

The fur trade was central to the continent’s economic development; beaver was its first major export. By the 1600s, the animals had been hunted almost to extinction in Europe and Asia (to be used, in large part, for hats), but the unspoiled shores of America were teeming with them. The demand for animal pelts (mostly beaver but also skunk, raccoon, otter and fox) fueled colonization and Western expansion, as the British, French and Dutch vied for control of fur-rich regions. That, in turn, led to conflict between the Native American tribes that did much of the hunting, trapping and trading. By 1730, the Hudson’s Bay Company, now the owners of Saks Fifth Avenue and Lord & Taylor, was exporting 39,000 beaver pelts per year.

America’s first millionaire, John Jacob Astor, also made his fortune in “soft gold,” an ascent that remains a fable of immigrant ambition and hustle. Taking in the splendor of the Astor House hotel, which opened in 1836, the frontiersman and politician Davy Crockett is said to have exclaimed: “Lord help the poor beavers and bears!”

And indeed, within the century the American beaver had become virtually extinct. But coats and robes of buffalo were coming into vogue, and their demand grew rapidly with the arrival of the steam engine, according to “Fur, Fortune, and Empire.”

From the end of the 1830s to the 1860s, some 90,000 buffalo robes were sent to St. Louis, then the largest fur trading hub in the country. (The U.S. Army also had a vested interest in the destruction of buffalo, thinking it might bring about a similar eradication of Native Americans people. In 1868, General William Tecumseh Sherman advised his fellow commander, General Phillip Sheridan, to “invite all the sportsmen of England and America” to the far reaches of Nebraska to hunt down the buffalo in order to deprive Native Americans of food.)

In 1837, the St. Peters, a steamboat operating on behalf of Astor’s American Fur Company, traveled from Missouri through the Dakotas with hundreds of bison robes and more than a few smallpox-ridden sailors on board. Every post the steamboat visited developed an outbreak of the illness, which reportedly left individuals feverish, blood pouring from their ears and mouths; the epidemic eventually claimed more than 17,000 native lives, most of them belonging to the Mandan, Minataree, Arikara, Sioux Assiniboine and Blackfoot tribes.

One observer at Fort Union, in what is now North Dakota, wrote: “The prairie has become a graveyard. Its wildflowers bloom over the sepulchers of Indians.”

By 1889, the buffalo, which once numbered 30 to 60 million, amounted to little more than 1,000. Their disappearance in large part prompted the modern conservation movement. Laws were enacted to establish national parks and protect game animals and gradually the fur trade evolved from an industry of hunting and trapping into one primarily dependent on farmers.

Enslaved black people and freedmen also participated in the old fur economy: Jean Baptiste Point DuSable, a black fur trader, established a successful trading post in the late 1770s that eventually became Chicago; George Bonga, a fur merchant, was one of the first free black people born in what is now Minnesota. James P. Beckwourth, a fur trapper and frontiersman, established a route through the Sierras at the beginning of the California Gold Rush.

Black women seem to have entered this history through hand-me-downs. In her book “Telling Memories Among Southern Women,” the archivist Susan Tucker writes that gift-giving (usually of secondhand domestic wares, furniture or clothing) from a white employer to her black maid was a showy testament of a lady’s generosity, and frequently a substitute for increased pay or fair wages. My mother recalls my grandmother speaking of several black maids who got their furs this way.

But the 20th century saw tremendous shifts in black cultural and political life. The artistic and literary fruits of the Great Migration, like jazz music and the Harlem Renaissance, brought new modes of self-expression. Celebrities and citizens both dripped with new Negro refinement and verve.

The era is exemplified in a 1932 photo by James Van Der Zee, titled “Couple in raccoon coats.” In it, a black man and woman dressed in matching, sumptuous furs pose in front of a car parked in front of a brownstone, a picture of urbane elegance. Their distinctly American consumerism appears bittersweet and courageous, a display of affection for a country which had never returned the favor.

In 1939, the opera singer Marian Anderson, the “colored contralto,” was refused a performance space at Constitution Hall in Washington D.C., so she performed on the steps of the Lincoln Memorial instead. She sang “My Country, ’Tis of Thee” wearing a classic mink coat, deep espresso brown, embroidered in gold thread, with her initials monogrammed inside. The coat seemed to steel her, offering protection from many bitter elements.

Billie Holiday, too, wore fur for performing and for protection. Arrested for drug possession in San Francisco in 1949 (she was later acquitted), Ms. Holiday showed up to her booking in sunglasses, with her hair turban-wrapped and a mink coat on her back.

In the 1960s, as black people began to appear in advertising as people and not just illustrations on food packaging, a mink conglomerate developed one of the most enduring campaigns in American retail history. Black stars like Diana Ross, swathed in a mille-feuille of black fur, hair sultrily flipped, and Ray Charles, beaming and bow-tied, were photographed as icons for Blackglama Mink. The tagline was: “What becomes a legend most?”

III.

PETA was founded in 1980 and quickly became famous for obtaining covert footage of mistreated animals: farm animals, shown in squalor, maddened by captivity and chewing at themselves and the bars that contain them; furred animals, electrocuted, boiled, clubbed, thrashed, crushed and poisoned; creatures tortured, sometimes protracted and painfully. The image of a bloodied creature, denuded of its fur and twitching on the ground, is a hard one to forget.

“We like to think of ourselves as P.R. for animals,” Ben Williamson, who was at the time PETA’s senior international media director, said in an interview last year.

But to champion animal liberation, PETA has repeatedly invoked human suffering, specifically, that of marginalized communities. The plight of livestock animals has been compared to Holocaust victims; captive whales at SeaWorld have been likened to chattel slaves.

In 2005, a PETA exhibition juxtaposed a photo of a black civil rights protester being beaten at a lunch counter with images of a seal being bludgeoned. Another piece from the show, titled “Hanging,” paired a graphic photo of a white mob surrounding two lynched black people, their bodies hanging from tree limbs, with the image of a cow in a slaughterhouse. In 2007, in an advertisement, the organization compared the American Kennel Club to the Ku Klux Klan.

“A chicken is a cow is a mink is a boy,” Mr. Williamson said. But PETA’s advocacy does not extend to people.

In 2008, the organization took it a step further, and antagonized Aretha Franklin with a cruel open letter. “Music lovers may think of you as a ‘queen,’ but to animal lovers, you are a court jester,” the letter, attributed to the vice president of PETA, said. “I’m sorry, Aretha, but your furs make you look like a clown. Why not shed the old-fashioned look that adds pounds to your frame and detracts from your beautiful voice?”

IV.

A Wisconsin family, the Zimbals, owns one of the largest mink farms in the United States. When I visited one of their minkeries in Sheboygan, Wis., last winter, I was greeted by Valerie Zimbal, the daughter of one of the farm’s co-owners, Bob Zimbal. She was wearing a dapper mink bomber jacket dyed lavender, with deeper violet accents. “I’m so glad you’re visiting us,” she said. “I wish more people did.”

The structures that house the mink resemble industrial greenhouses. The sides and roofs have automated panels, so that the temperature inside is adjustable. Each holds about 2,700 animals. Upon entering the facilities, we all donned white paper suits and disposable shoe coverings.

A large drum, with carbon monoxide piped in at a lethal concentration, holds the mink as they are exterminated during culling season, which will arrive later in the fall. According to Mr. Zimbal, the animals are stunned and unconscious within five seconds, and dead in less than minute. The very best mink, those with the most lustrous coats, will be spared and bred again next season; those with coats which are impressive, but not premium, will be killed, their hides sold at a national fur auction.

As I walked through each row, mink would approach the front of their cages, their button noses twitching in mammalian curiosity. Their wee forepaws resembled hands. They were, in a word, cute.

Lately, the fur industry has gone on the defensive, seeking to challenge the reflexive labeling of their business as innately unethical and ecologically irresponsible. Mr. Zimbal argued that his farm was better for animals (commercial farming allows wild populations to flourish) and sustainable, considering the environmental hazards of plastic and acetone derived faux fur.

At the Zimbal minkery, every item of the animal’s body is used, he said. The skin is pressed to produce mink oil, which repels water and is an additive in cosmetic products. Mink meat is used in pet food, and mink droppings are sent to farms nearby to use as compost. The mink are fed with undesirable bits of other livestock: the hearts of pigs, the lungs or bladders of cows, and substandard eggs.

Fur farmers have a financial interest in lessening their environmental strain: A too-warm planet may mean citizens who no longer need fur. Though Chicago this week resembled the Arctic, my mother noted that her coats have had to spend more and more time in cold storage, as the weather has been too temperate in recent years to wear them out.

The last time she wore a fur, the fox, it was in November, to attend a cousin’s funeral. She looked like the only person dressed with the pomp that the occasion, and her cousin’s life, warranted. I remember thinking that my own wool blend looked insufficient in comparison. So often the commercial habits of black people are demonized. The image of a black woman, heading to church or some other event, enveloped in her fine fur, remains one of the most enduring and affecting totems of resilience and glamour in the black urban landscape.

My mother’s furs are her insistence on public elegance in a world frequently inhospitable to her. It is a point of pride that she wears, and will pass down to me.