This article is part of our Design special section about new interpretations of antique design styles.

Some forms of architecture and design, produced through arduous or even backbreaking labor, can be thought-provoking or perhaps even discomfiting to study, while also enduring as role models. Four new books explore such places and objects, while paying tribute to 18th-century Austrian quarrymen, enslaved workers before the Civil War, Tunisian beachcombers and modern weavers.

Joseph McGill Jr., the founder and executive director of the Slave Dwelling Project, a nonprofit group, has spent hundreds of nights in American rooms that Black people held in slavery constructed and occupied in the antebellum period. “Sleeping With the Ancestors: How I Followed the Footprints of Slavery” (Hachette, $29, 337 pp.), written with the journalist Herb Frazier, chronicles how Mr. McGill negotiated with officials and landowners for access to historic buildings and coped with opposition to the project. At sites scattered from Texas to the Hudson River Valley in New York, Mr. McGill has brought along groups to share the emotionally fraught experiences; some of his companions have worn shackles all night, trying to fathom their enslaved ancestors’ torments.

The book searingly describes dirt-floored cabins besieged by mosquitoes and creaky, airless attics, and it delves into the biographies of the properties’ past inhabitants. As Mr. McGill’s teams spent largely sleepless hours in these quarters, they grew hyperobservant, noticing for instance where a plastered wall was striped with “shadows from the magnolia near the window.” Mr. McGill has paid particular attention to brickwork; the clay, he writes, remains textured with “finger-shaped impressions” from enslaved brick makers.

Gathering ingredients for textile dyes can be brutal, lethal work, documented by the designer and researcher Lauren MacDonald in “In Pursuit of Color” (Atelier/D.A.P., $49.95, 240 pp.). She analyzes practices dating from thousands of years for pulverizing flora, fauna, fungi, fossils and fuels into potions for saturated hues. Blood, urine and dung have been required by the barrel. Alligators have attacked underpaid or enslaved laborers seeking logwood for black dyes in Yucatán swamps. Lichens for inducing purple shades were found on Azores rock faces accessible via baskets dangling from ropes — one hazardous spot for climbers became known as the Cliff of the Fallen.

By the 1860s, mass-production techniques worsened conditions for dye workers and their neighbors; one Swiss factory specializing in magenta flooded the surrounding soil and water supply with arsenic-laced “brown-violet liquid,” Ms. MacDonald writes. She also reports on modern preservers of sustainable traditions. The Tunisian expert Mohamed Ghassen Nouira, for example, has revived the ancient and malodorous art of extracting purple dyes from crushed murex seashells, while thriftily using the snail meat to make breaded snacks.

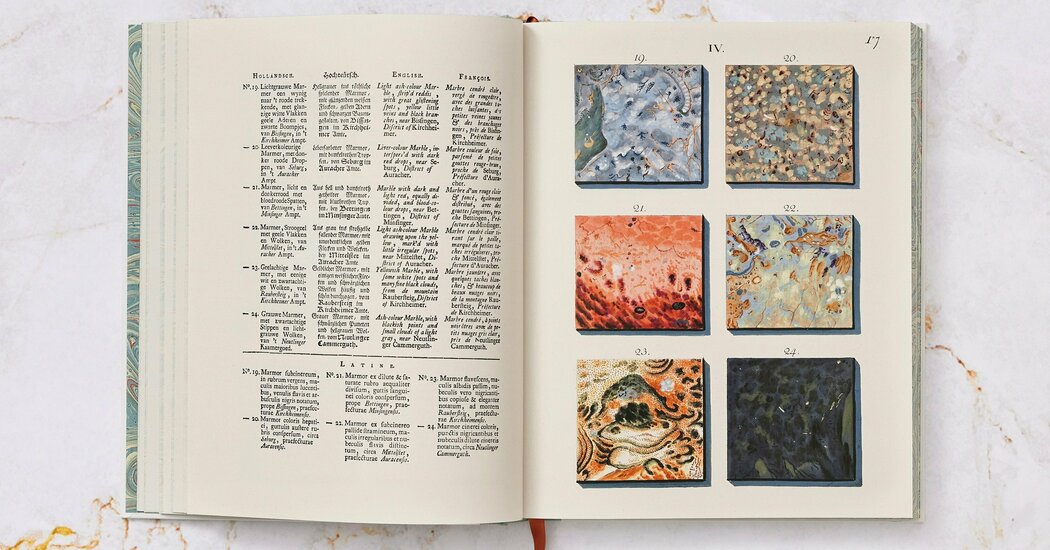

“We shall not cease to seek for new discoveries,” Jan Christiaan Sepp, an Amsterdam book publisher, promised in the 1770s, while issuing a lavish multilingual tome titled “A Representation of Different Sort of Marble.” Its kaleidoscope of hand-tinted engravings depicts about 570 samples of stone quarried in Austria, Germany, Switzerland, France, Italy and the Netherlands. It has been facsimiled and slipcased as “The Book of Marble” (Taschen, $125, 312 pp.), with a new essay by the book expert Geert-Jan Koot.

The original edition of about 100 copies circulated among Enlightenment academics and collectors as well as builders and designers. Mr. Sepp commissioned detailed descriptions from Casimir Christoph Schmidel, a physician and naturalist. He noted which kinds of matte marble resisted polishing, and where rich deposits could be found underwater or alongside particular castles or pastures. For anyone with “a fertile imagination,” he wrote, veiny patterns and embedded crystals and fossils might resemble birds, trees, fish eggs, tinsel, ruined buildings or contour maps.

In a five-decade career starting in the 1920s, the textile designer Dorothy Liebes (pronounced LEE-bus) emphasized tactility, luminousness and contrast by combining natural and synthetic fibers in neon shades. For clients and collaborators as prominent as Frank Lloyd Wright and the fashion designer Bonnie Cashin, her studios in Manhattan and San Francisco alchemically interwove bamboo, cellophane and aluminum. Journalists, photographers and filmmakers descended on her rows of looms, operated by workers hired “regardless of their immigration status, gender, race, ethnicity or sexual orientation,” the curator and scholar Erica Warren points out in “A Dark, A Light, A Bright: The Designs of Dorothy Liebes” (Yale University Press, $50, 253 pp.).

The book, with essays by seven experts and a comprehensive biographical timeline, accompanies a Liebes retrospective that runs through Feb. 4 at the Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum in New York. Ms. Liebes, although underappreciated now, practically blanketed the world with products while battling corporate misogyny. Factories adapted her handwoven samples for mass-market clothing and furnishings, and she lined mansions and offices with sumptuous one-offs. At one Texas bank, her shimmery draperies were named Pretty Penny and Pennies from Heaven.