Although a vaccine for dementia is a long way down the road, researchers recently made a few tentative steps closer. The authors of a recent study in mice hope that in the coming years, they can move into human trials.

Globally, dementia affects an estimated 50 million people. Because dementias are primarily a disease of older age, this figure is likely to increase as the average life expectancy increases.

In fact, some scientists have calculated that the burden of dementia in the United States could double by the year 2060.

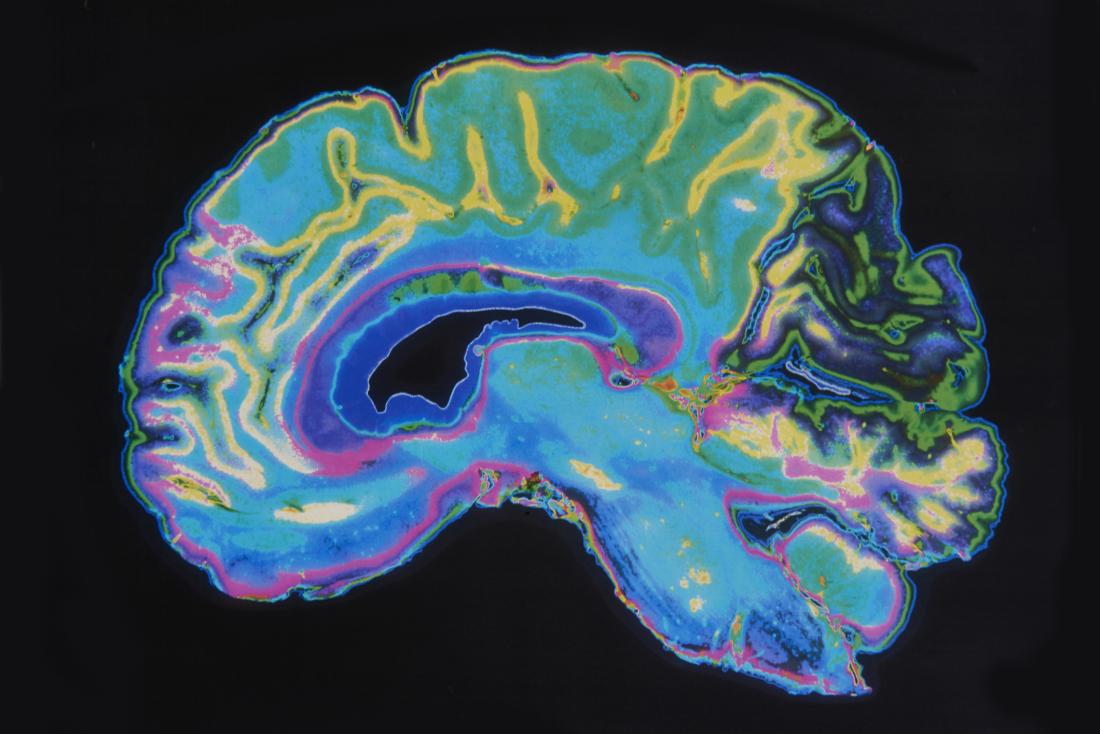

Alzheimer’s disease, which is the most common form of dementia, is characterized by changes in the brain. Specifically, there is a buildup of beta-amyloid, which is a protein that produces amyloid plaques. Similarly, another protein, known as tau, accumulates to form neurofibrillary tangles. Together, these proteins drive cognitive decline and neurodegeneration.

Currently, there is no cure for dementia, and treatments are limited. Over the years, several promising drug candidates have proven unsuccessful in human trials.

A preemptive strike

The authors of the current study believe that one of the reasons that experimental drugs have failed is because treatment is “initiated too late in the pathological process.”

They believe that once the disease mechanism is in full swing, it is more difficult to bring the brain back into a healthy state.

With this in mind, scientists are focusing their energy on developing vaccines that they can use before symptoms arise, stopping dementia in its tracks. The most recent study along these lines is now available in the journal Alzheimer’s Research & Therapy.

The authors, from the University of California, Irvine, and the Institute for Molecular Medicine in Huntington Beach, CA, investigated a combination vaccine approach.

Scientists believe that the combination of beta-amyloid plaques and neurofibrillary tangles might work together to speed up neurodegeneration. The authors of the recent study explain that these two distinct pathologies “may interact to trigger the progression from […] mild cognitive impairment” to Alzheimer’s disease.

With this in mind, the researchers attempted to target both types of protein accumulation at once. They hoped that by hitting both targets, they might be more successful than the drugs that only approach one at a time.

A new vaccine

Earlier studies in mice have demonstrated that two vaccines, known as AV-1959R and AV-1980R, produce an antibody response to beta-amyloid and tau, respectively. In the new study, the authors investigate their combined effect.

The scientists carried out their research using mice that develop pathological aggregates of tau and beta-amyloid. They developed a vaccine consisting of both AV-1959R and AV-1980R.

Importantly, the scientists delivered these drugs alongside an adjuvant called AdvaxCpG, which helps produce a stronger immune response in animals that receive the vaccine. Another author of the current paper, Prof. Nikolai Petrovsky from Flinders University in South Australia, designed this adjuvant.

As expected, the researchers found that the combination therapy induced the production of antibodies to both tau and beta-amyloid. In turn, these antibodies reduced levels of the insoluble tau and beta-amyloid that produce plaques and tangles. The authors conclude:

“Taken together, these findings warrant further development of this vaccine technology for ultimate testing in human [Alzheimer’s disease].”

Because scientists have already shown that these types of vaccines and adjuvant are safe in humans, they hope that they might soon take this research to the next level. The authors believe that within 2 years, they could bring this two-pronged vaccine to clinical trials.

Because so many previous attempts to treat dementia have failed, it is important to approach this recent study with caution. However, the suggestion that a vaccine for dementia might be on the horizon is a reason to be excited.

Earlierattempts to design a dementia vaccine have, similarly, produced positive findings but are yet to bear fruit. Although this most recent study builds on previous work and has several factors in its favor, only time will tell whether it will be effective in humans.