Cancer immunotherapy drugs, which spur the body’s own immune system to attack tumors, hold great promise but still fail many patients. New research may help explain why some cancers elude the new class of therapies, and offer some clues to a solution.

The study, published on Thursday in the journal Cell, focuses on colorectal and prostate cancer. These are among the cancers that seem largely impervious to a key mechanism of immunotherapy drugs.

The drugs block a signal that tumors send to stymie the immune system. That signal gets sent via a particular molecule that is found on the surface of some tumor cells.

The trouble is that the molecule, called PD-L1, does not appear on the surface of all tumors, and in those cases, the drugs have trouble interfering with the signal sent by the cancer.

The new study is part of a growing body of research that suggests that even when tumors don’t have this PD-L1 molecule on their surfaces, they are still using the molecule to trick the immune system.

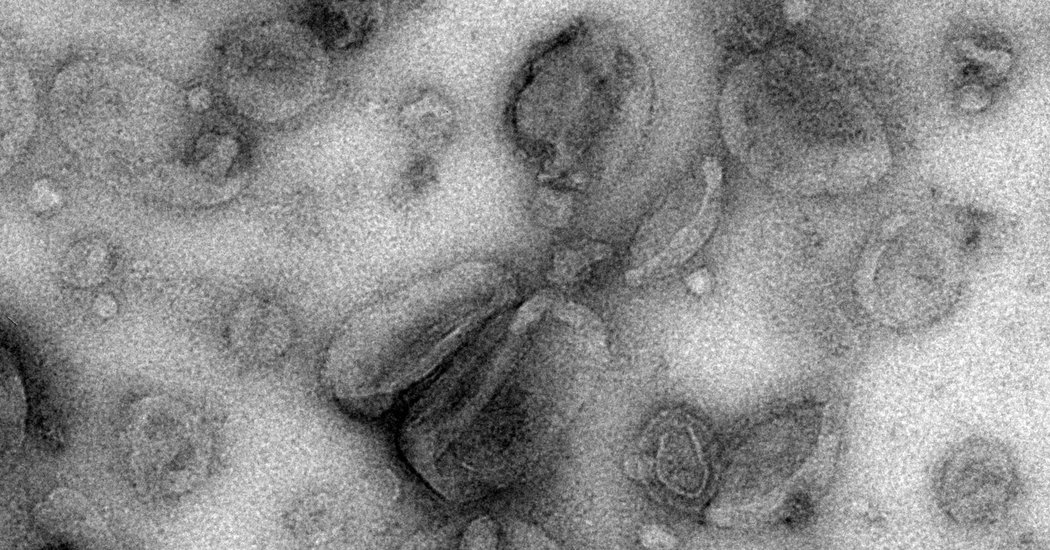

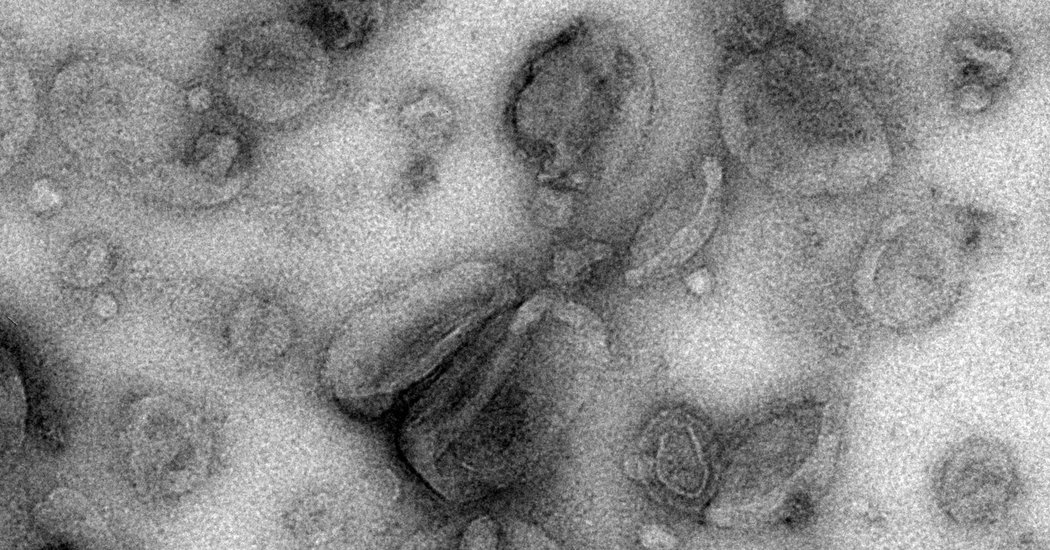

Instead of appearing on the surface, the molecule is released by the tumor into the body, where it travels to immune system hubs, the lymph nodes, and tricks the cells that congregate there.

“They inhibit the activation of immune cells remotely,” said Dr. Robert Blelloch, associate chairman of the department of urology at the University of California, San Francisco, and a senior author of the new paper.

The U.C.S.F. scientists discovered that they could cure a mouse of prostate cancer if they removed the PD-L1 that was leaving the tumor and traveling to the lymph nodes to trick the immune system. When that happened, the immune system attacked the cancer effectively.

Furthermore, the immune system of the same mouse seemed able to attack a tumor later even when the drifting PD-L1 was reintroduced. This suggested to Dr. Blelloch that it might be possible to train the immune system to recognize a tumor much the way a vaccine can train an immune system to recognize a virus.

The work was done not in humans but in laboratory experiments and in mice, and it is not clear whether the results will translate in people. Dr. Ira Mellman, vice president of cancer immunology at Genentech, called the findings “a most interesting result.”

“But as with all mouse experiments, you get insight into basic mechanisms, but how it translates to the human therapeutic setting is unclear,” said Dr. Mellman. He is skeptical, he said, but plans to meet shortly with Dr. Blelloch to discuss the implications of the work.

The new research dovetails with other recent studies, including a paper published last year in the journal Nature that showed that PD-L1 molecules released from skin cancer tumors can suppress the body’s immune function.

When these bits of PD-L1 travel outside the cell, they are known as exosomal, and the discovery of their role is one of many fast-moving developments refining an area of medicine that has become among the most promising in decades.

Late last year, the Nobel Prize was awarded to two scientists — James P. Allison of the M.D. Anderson Cancer Center in Houston, and Tasuku Honjo of Kyoto University in Japan — who did groundbreaking work in immunotherapy.

An explosion of additional research is aimed not only at refining the therapies — which can have profound side effects — but also at searching for other molecules involved in the perilous dance between cancer and the immune system.

Far more study is needed. But Dr. Blelloch said the findings have him looking for ways to take the next steps into turning the discovery into a concrete therapy.

Interfering with the PD-L1 traveling to lymph nodes “can lead to a long-lasting, systemic, anti-tumor immunity,” the paper concluded.